How About A Game Dinner?

Nothing is more American than sitting down to a meal with seventy of your favorite wild animals.

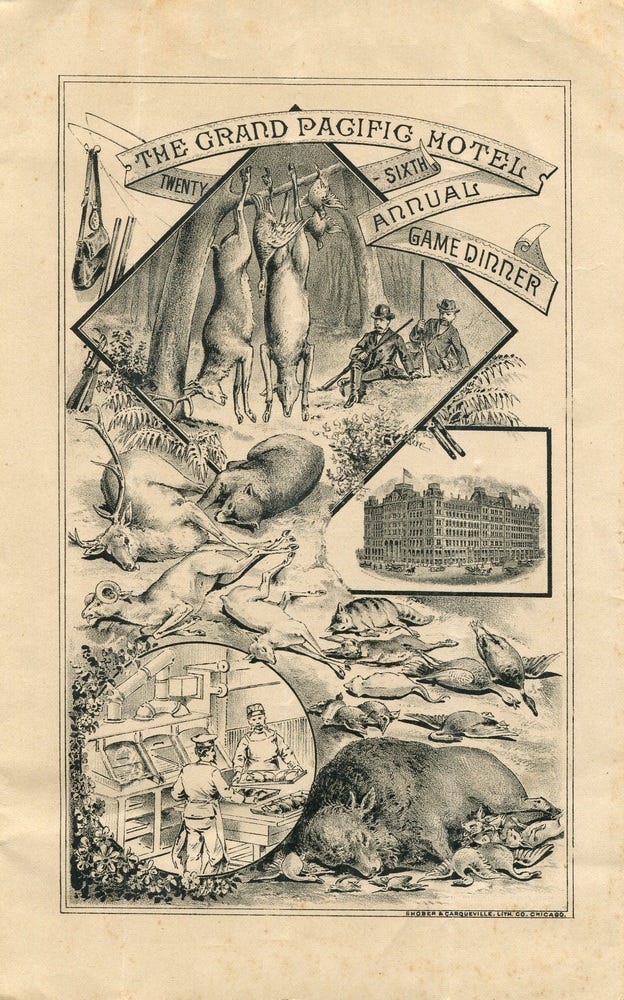

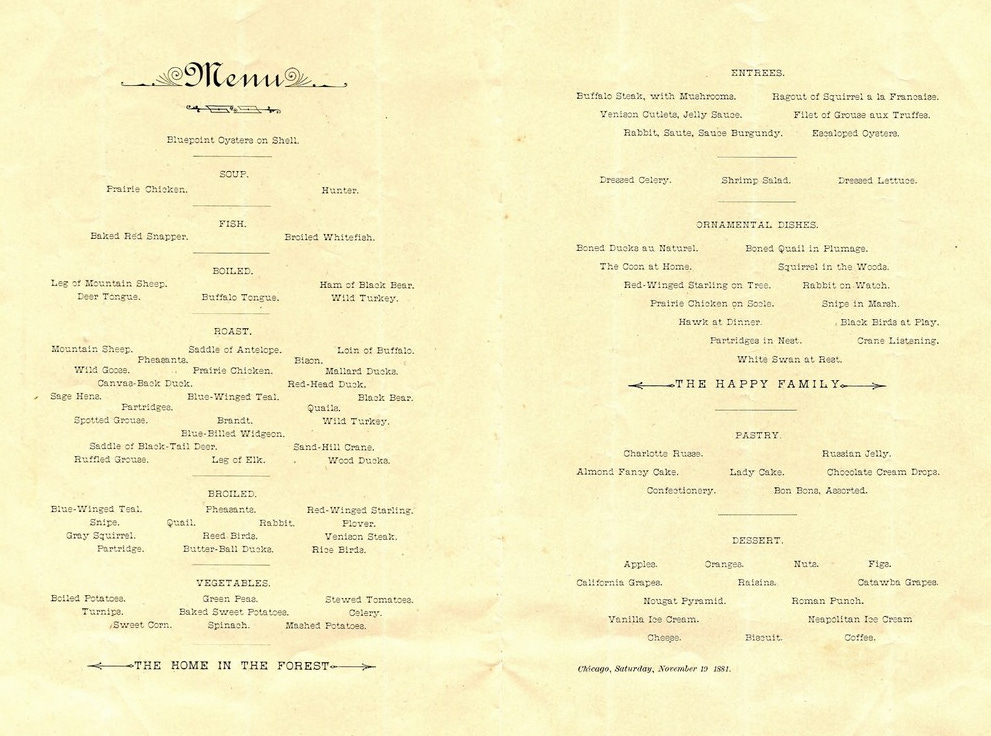

As soon as the five hundred gown- and tuxedo-clad guests filed into the great hall of Chicago’s Grand Pacific Hotel, they stood face to face with about seventy different kinds of animals that they would soon eat. For the last twenty-eight years, John Drake had served Chicago’s leading citizens an annual game dinner that each year grew in size and diversity, and the 1883 dinner would be no exception. Just inside the great hall’s doors Drake had constructed a mountain in miniature, decorated with trees, shrubbery, and dozens of posed animals, representing many of the animals on the menu. Each dining table featured a centerpiece of wild animals, “a perfect embodiment of the hunter’s victims, roasted yet as if living”—turkeys, prairie chickens, partridges, blackbirds, grouse, raccoons, ducks, squirrels, “and divers other toothsome denizens of the wood and field,” not taxidermied, but rather roasted, then posed with wires, then covered back up with their fur or feathers, waiting for diners to disrobe and then carve.1

Beside each centerpiece, guests found an elaborately-decorated menu listing the animals who had given their lives for the occasion, including but not limited to: fox squirrel, gray squirrel, whitefish, black bass, black bear, blackbird, buffalo, cinnamon bear, silver-tip bear, mountain sheep, antelope, elk, raccoon, opossum, jackrabbit, English hare, Canada goose, canvasback duck, black duck, gray duck, dusky duck, wood duck, longtail duck, pintail duck, mallard duck, gadwall duck, shoveler duck, scaup duck, butterball duck, buffle-headed duck, bobwhite, golden plover, prairie chicken, reed birds, rice birds, ruffed grouse, pin-tailed grouse, sparrow, snipe, brant, pheasant, oysters, and turtle.

Then there were the ornamental dishes. Diners could look around the room and spot: “Pyramid of Game, en Bellevue; Boned Quail, in Plumage; Red Winged Starling, au Naturel; Pin-tailed Grouse in Feather; Rabbit Watching the Hunter; Blackbirds on Tree; The Coon at Home.” One newspaper confidently declared, with some reason, that John Drake’s event was “undoubtedly the grandest game dinner ever given in the United States.2

By this point, John Drake’s game dinners were, according to an 1886 article in the St. Paul Daily Globe, “almost as much an institutional part of Chicago as the stock yards.” The historian David Shields considered them the most famous culinary events of Gilded Age America. Drake put on his first game dinner back in 1855, when he was 29 years old and when Chicago was just 18. That year, he bought an ownership share of Chicago’s most prominent hotel, Tremont House, and began his tenure as proprietor with dinner served to fifty guests and comprising a relatively modest twenty species of game, including venison, prairie chicken, quail, wood duck, rabbit, turkey, passenger pigeon, mallard, teal, widgeon, canvasback, snipe, sandhill crane, and bear. Every subsequent year he made it his professional obligation to expose his diners to an ever-greater assortment of game.3

When Tremont House burned down in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, Drake, like the city, built back bigger and better. He took over management of the newly-built Grand Pacific Hotel where he resumed his game dinners on a scale which he hoped would make up for their four-year absence. His first year back, one reporter editorialized that his chefs “vigorously studied Cuvier, Audubon, Wilson, Buffon, and Baird, in the hope that they might find some member of the animal kingdom that flew in the air, ambled upon the earth, or lived in the sea, hitherto unheard of, to be added to the ‘game dinner’ bill of fare as a surprise.”4 The resumption of this feast in a hotel rising from the ashes came to represent Chicago’s resiliency, and thereafter became a highly-anticipated civic ritual.

As Chicago’s suburbs and stockyards filled in the marshes and prairies where Drake had once sourced his game, the city’s growing network of railroads made it just as easy to ship fresh and frozen game from the Chesapeake or California as from Illinois. “The position of Chicago on the prairies and within easy reach alike of the seaboard and the great plains, gives her gastronomes exceptional advantages,” said one writer in the sporting magazine Forest and Stream.5 Its location and stockyards made Chicago the game capital of America.

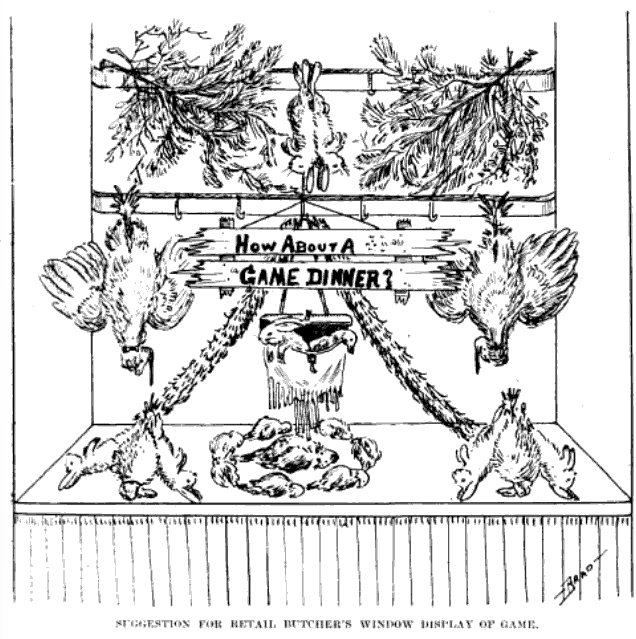

It wasn’t just the lucky attendees of Drake’s dinners who ate woodcock and quail, of course. Markets throughout the country offered a wide selection of wild birds and mammals to anyone who fancied eating them. But the game dinners offered by upscale hotels and restaurants meant more than gathering around a carved turkey. These were celebrations—one could say orgies—of America’s abundant wildlife, and their reputation extended around the world. In 1898 the Australian magazine Table Talk called game dinners “an American institution.”6

In the 19th century, America’s cuisine was synonymous with its game, best displayed not through an accomplished command of technique or masterful use of spices, but through its seemingly limitless number and diversity of edible animals. To honor the visit of British minister Lord Napier to the US Capitol in 1859, for example, the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. served 1,800 guests a grand banquet of “canvas-back ducks from the Delaware, reed birds from the Savannah, wild turkeys from Kentucky, prairie hens from Iowa, mutton from the Cumberland mountains, venison from North Carolina, and other ‘native American’ dishes.”7

Game dinners represented the wildness that defined America, all gathered together on a banquet table. America’s identity was bound up in its rapidly-receding frontier. By 1890, the U.S. Census Bureau declared the frontier closed, passenger pigeons had just about disappeared from the wild, and bison seemed destined for the same fate. But railroads were still shipping ducks and prairie chickens from the Great Plains to coastal cities by the ton so that diners in New York and Boston could still take a bite of something American, something wild.

Newspapers throughout the country discovered that Drake’s game dinners made great copy, and in breathless paragraphs they emphasized that the entire country’s resources were encapsulated in one night’s menu:

“All the fowls that cleave the clouds from the lakes to the gulf, all the beasts that ruminate over the broad plains of the Southwest, or run wild in the rocky fastnesses of the Sierras contributed to the feast. Reed birds and rice birds from the dank marshes of the sunny South; quails, prairie chickens, jack snipes, plovers and partridges from the Illinois meadows; blue-winged teals and butterball ducks from the crystal lakes of Wisconsin and Minnesota; brants from the far north, sage hens from the Colorado plains, wild turkey and gray squirrels from the forests of the Northwest, a whiff of Northern pinelands, a reminiscence of magnolia blooms from Southern forests—all these were there.”8

But as the century wore on, game was not quite so available as it always had been, and Drake was forced to draw from far-flung lakes and marshes out of necessity. This was not a welcome development among the gentlemen hunters who made up the sporting class, who were becoming ever more critical of the market systems that brought these beasts to the insatiable urban masses and in the process drained the country of the animals which sportsmen were finding increasingly difficult to find. One sportsman complained that “for the dinner of 1888, as may be seen, [Drake] fairly ransacked the Rockies to the sea.”9

By this point, Drake was getting old and tired. He couldn’t keep up these logistical and culinary feats much longer, and the advance of laws advocated by sportsmen to end the commercialization of wild animals made it more challenging, and often legally dubious, to procure the same game he’d purchased in years past. Another sportsman wrote of the 1891 dinner, that “unless Mr. Drake was fortunate enough to have his quails, prairie chickens and partridges given to him by admiring friends, he broke the game law of Illinois, which forbids their being sold at any time.”10 Drake served his last game dinner in 1893, and he died the following year. He would host a total of 38 of these dinners, which would never again be equaled.

To be clear, sportsmen were not opposed to game dinners themselves. What they objected to was the way proprietors like John Drake sourced their meat. Wild animals were not meant to be bought and sold, they believed, but rather hunted in a sportsmanlike way. A true sportsman, instructed J. H. Langille in 1895, hunts by “shooting only game proper, and that is never out of season, taking an animal on the run, and the bird on the wing in order to give each a chance for its life.”11

Unlike Drake’s massive, commercial, public affairs, sportsmen had their own take on the game dinner. Beginning in the 1840s, sportsmen had begun organizing into clubs and associations to advocate for the protection of game, proliferating to more than 954 organizations throughout the country by 1891. Like many of these clubs, the Lackawanna Game and Fish Association, based in Scranton, Pennsylvania, formed in response to “the rapid development of this section, with its consequent inroads upon fish and game, threatening their utmost extinction.” Association members supported the cause of game protection by distributing summaries of the state’s game laws to farmers, stocking local lakes with trout and salmon, and planting wild rice in lakes to attract wild ducks.12

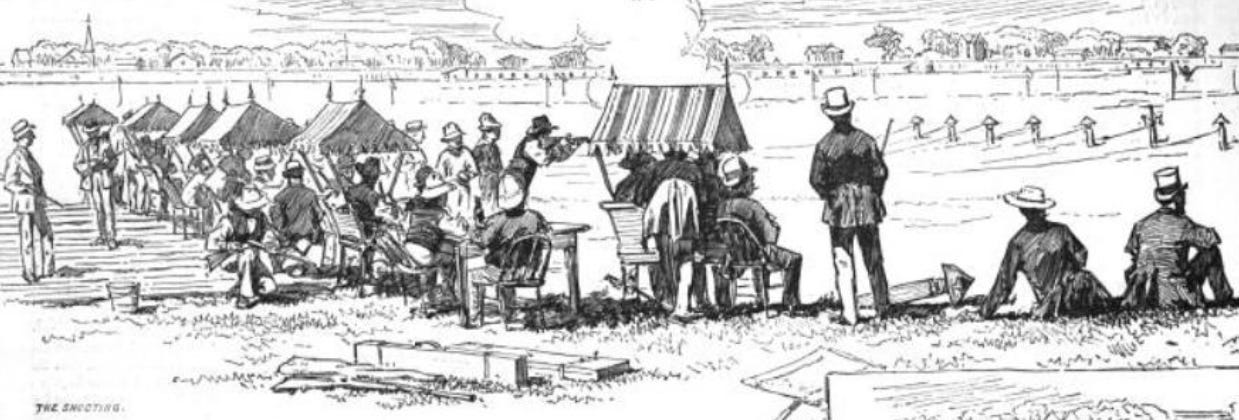

But at its core, sportsmanship was about recreation, and the Lackawanna Game and Fish association did plenty of that too. For the Lackawanna club, like most other clubs throughout the country, the main event on their social calendar was the annual assembly, which was frequently paired with a pigeon shooting contest or a game dinner, and featured “every seasonable dish of game indigenous to this locality as well as a notable contribution from friends at the Far West.”13

The food for these dinners was often procured through “side hunts,” where club members divided up into teams and competed to see which side could kill the most animals over one or two days. Similarly, the New Orleans Gun Club challenged the Montgomery, Alabama Gun Club in October, 1877 to “join in a grand competitive shooting match for a game dinner.” At the conclusion of their shoot, all the animals they’ve killed would be “counted and turned over to a favorite restaurant, to be served up in a banquet, the losing club paying all the expenses.” Under their scoring system, robins would be worth 1 point; doves, 2; snipe, 8; quail, 10; mallards, 15; squirrels, rabbits, and other ducks, 10; hawks or owls, 25; woodcock, 25; prairie chickens, 30; geese, 50; turkeys, 250; deer, 500; bear, 1,000.14

Many of these clubs proved far more effective at shooting game than protecting it, as suggested by op eds sent by critical sportsmen to Forest and Stream, like one from 1880, which reads “The large clubs of New York and vicinity, both for shooting and the protection of game, seem to have entirely lost sight of the real object of their organization and have degenerated into a system of periodical dinners and post prandial bombastry.”15

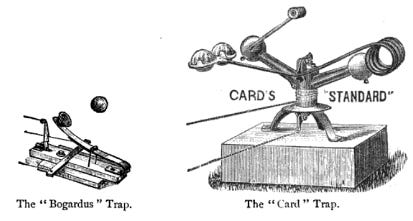

These tensions led to a rift at the 1880 annual dinner of the Worcester Sportsmen’s Club of Massachusetts. Following a successful campaign by the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals to ban the sport of pigeon-shooting, members of the sportsmen’s club narrowly voted to have a glass ball shooting competition (precursors to the clay pigeons that trap shooters target today) rather than their traditional annual side-hunt.

But “although the day was simply perfect . . . . this departure of the club from the old custom was by no means satisfactory to a large number of the members,” who decided to go ahead and have their “old-time hunt and dinner” regardless. These rump sportsmen went ahead with their shoot, split into teams, slaughtered all the game they could find, and laid out their haul on a long table to be counted and scored. The pile of animal carcasses brought back by Captain Houghton’s side added up to 1,360 points, and they were declared the winners. Then the two sides reunited for dinner at the Bay State House where they ate the piles of partridges, woodcock, and quail they’d shot, augmented by deer, antelope, goose, and buffalo tongue sent by one A. B. F. Kinney, “who had just returned from his Western hunting trip on the excursion car ‘Jerome Marble.’”16

Unsurprisingly, the sort of hunting that supplied game dinners, both by market hunters and by relatively unrestrained sportsmen, was unsustainable for wildlife, and with good reason these orgiastic game dinners seem like a relic of a less prudent time. But one artifact from the game-dinner era is still very much with us. In 1900 the ornithologist Frank Chapman proposed the Christmas Bird Count as an alternative to the sportsmen’s side-hunt competitions, a festive and competitive wintertime census that would count birds rather than kill them. The CBCs, as they’re abbreviated, have proven to be incredibly valuable resources for tracking long-term trends in bird abundance. What started as game dinners has become the longest-running citizen science survey in the world.

“Drake’s Game Dinner.” Chicago Legal News. November 24, 1883, p. 91; “An Epicurean Banquet.” The Daily Inter-Ocean, November 24, 1879, p. 8; “A Gastronomic Triumph.” The Daily Inter-Ocean, November 12, 1877, p. 8.

“Drake’s Game Dinner.” Chicago Legal News. November 24, 1883, p. 91.

“Drake’s Game Dinner.” St. Paul Daily Globe, November 21, 1886, p. 12; Shields, David S.. The Culinarians: Lives and Careers from the First Age of American Fine Dining. United Kingdom: University of Chicago Press, 2017; “Game Dinner.” The Daily Inter-Ocean. November 15, 1880, p. 8.

“Drake’s Game.” The Daily Inter-Ocean, November 15, 1875, p. 2.

“A Game Dinner.” Forest and Stream. December 6, 1877.

“Decorations and Menus for Game Dinners.” Table Talk. United States: Arthur H. Crist Company, December 1898.

“The Napier Ball,” Harper’s Weekly, Volume 3, no. 113, February 26, 1859, p. 134.

“Chicago and the West.” Forest and Stream, December 8, 1891, p. 389.

“Chicago and the West.” Forest and Stream, November 29, 1888, p. 365.

“Chicago and the West.” Forest and Stream, December 8, 1891, p. 389.

Langille, J. H. “Our Birds.” Fifty-Fourth Annual Report of the New York State Agricultural Society for the Year 1894. Albany: James B. Lyon, State Printer. 1895.

Wildwood, Will. “The Sportsman’s Directory.” United States: Fred E. Pond, 1891; “The Lackawanna Association.” Forest and Stream, December 23, 1880, p. 410.

“The Lackawanna Association.” Forest and Stream, December 23, 1880, p. 410.

“Game In Season In October: Louisiana.” Forest and Stream, October 18, 1877. p. 216; “New Orleans, Jan. 22.” Forest and Stream, January 31, 1884, p. 10.

“The Southampton Club.” Forest and Stream, December 23, 1880, p. 410.

“Notes from Worcester, Mass.” Forest and Stream, November 16, 1882, p. 308.

This is a bit of history that is...pardon the pun...difficult to digest. But I LOVE that you ended with the story of Frank Chapman turning the tradition on its head for the benefit of animals. Really great article!

As someone who studies Native history, the coincidence in time between this wanton shooting of birds, the deforestation of Eastern Woodlands and destruction of other habitats, and the ethnic cleansing and genocide of its Indigenous peoples, is impossible not to notice. They all seemingly rode the same wave, peaking in the mid- to late-1800s, and suddenly ending around 1890 with words of moderation and repentance, though changed actions have been slower in coming.