Bird Law

19th-century sportsmen tried litigating their way to bird protection. Would it be enough to save wildlife?

Every time I write a post, a lot of good material gets left on the cutting-room floor so I can meet my arbitrary self-imposed length limit. I’ve always thought that it was a shame that these tidbits, tangents, and delightful but not-quite-on-topic quotes never see the light of day. So I’m going to start experimenting with sending these extra pieces (bloopers? behind the scenes? director’s cuts?) to paid subscribers after each Substack post, which will always be free to read. Paid subscriptions start at just $6 per month, and also include a hand-made linocut print of your choice, which you can see at the bottom of this post.

When you took American History in high school, you probably learned that the country’s conservation movement began in 1872 with the creation of Yellowstone National Park. If you learned about conservation in college, you might have read that organized conservation work didn’t really start until 1887, when Theodore Roosevelt founded the Boone and Crockett Club to preserve large mammals like moose and bison. When I started writing this series on bird protection, I thought the story would begin the year before that, when the first Audubon Society was established.

But as I dug further, I learned that organized conservation work was underway long before Yellowstone and Audubon, decades before Theodore Roosevelt was born. I would even pinpoint the moment that America’s conservation movement began to May 20, 1844. On that date, eighty-something gentlemen gathered at William Senn’s house on the corner of Broome and Forsyth streets in Manhattan to form the New York Sportsman’s Club. Its secretary later explained that “The objects and pursuits of the club… are confined solely to the protection and preservation of game.” This now-forgotten association was the first organization dedicated to wildlife conservation in America.1

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how wealthy hunters around the country gained an understanding of their collective identity as sportsmen, something that they feared was under threat by the market hunters, free Blacks, and poor Whites who they blamed for clearing the countryside of game. Many states had a smattering of laws limiting hunting dating back to the colonial period, but these were unenforced and inadequate to reverse the disappearance of the country’s turkeys, quail, and woodcock. Now, this group of New York sportsmen, most of whom were lawyers by trade, realized that if the birds were to be saved, they would have to take matters into their own hands.

The New York Sportsmen’s Club immediately put its lawyers to good use. As one of its first actions, the club drafted a law banning spring hunting of woodcocks, quail, grouse, and deer, and introduced it to the county’s legislature. After New York’s board of supervisors passed the bill into law in 1846, the club launched an inquisition into restaurants and hotels selling game out of season and filed lawsuits against anyone found possessing illegal birds. The club’s report from October 6, 1846 gave a sense of their results. That week, they succeeded in obtaining a judgment against E. W. Thompson for ten dollars for illegally possessing two partridges, while Cafe Tortoni was made to pay five dollars for serving an out-of-season partridge and quail.2

Sportsmen throughout the country were just as concerned about the birds disappearing from their own back yards, and they recognized that New York’s model might be their best shot at preserving their beloved pastime. In quick succession, hunters from Maine to Michigan organized their own sporting clubs, keeping the New York club’s secretary busy with requests for advice on forming their own associations.

By 1864 there were more than a hundred local and state sportsmen’s clubs throughout the country, which to one degree or another lobbied their state legislatures to pass laws for the protection of game. State associations came together in 1874 to form a National Sportsmen’s Association, whose purpose was to “procure the passage of better laws to secure the preservation of game.” By 1891, the list of sportsmen’s clubs took up twenty-three pages in the Sportsman’s Directory.3

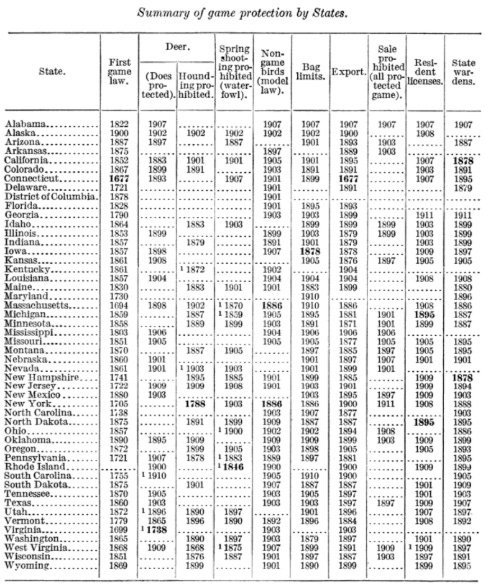

Sportsmanship had become part of the civic fabric of upper-class society. These wealthy hunters used their new-found political power to lobby state legislators to consolidate their haphazard assortment of hunting laws into coherent state game codes. Under their pressure, one state after another adopted the best practices that would eventually become keystone components of American game protection. New Jersey and Connecticut were the first states to protect non-game birds in 1850, for example, while Arkansas banned market hunting in 1875, and Iowa was the first to institute a state-level bag limit in 1878. By 1880, every state had passed laws to protect their birds, and under continual pressure from sportsmen, most states were augmenting their game laws almost yearly.4

Self-interest may have motivated hunters to rally for the protection of their prized woodcock and quail, but by expanding legal protections to non-game birds, they hinted at an emerging conservation ethic. In 1851, for example, Vermont imposed a one dollar fine for killing or taking the eggs of any “robin, bluebird, yellow-bird, cherry or cedar bird, catbird, kingbird, sparrow, lark, bob-o’-link, thrush, chickadee, pewee, wren, warbler, woodpecker, martin, swallow, nighthawk, whippoorwill, groundbird, linnet, plover, phoebe, bunting, humming-bird, tattler, and creeper.” Other states quickly followed suit, although they similarly struggled to define this broad group of small, innocent, and helpful birds. Most adopted language similar to New Jersey, which in 1885 banned killing or selling “any insectivorous or song bird.”5

Few groups were better equipped to lobby new laws into existence than sportsmen. Just like in New York City, many sportsmen’s clubs counted plenty of attorneys among their numbers, who were experienced in drafting laws and filing lawsuits. Some were themselves elected officials. Legislators were not their social betters, but rather their peers.

Their opponents, in contrast, were all far removed from the halls of power. The poor White squatter killing birds to feed his family; the recently-freed slave abusing his recently-obtained rights to blast away at birds much better suited to Whites; the illiterate and ill-mannered market hunter killing far more game than he deserved – none of these received much sympathy from wealthy White lawmakers, who at any rate thought that restrictive legislation could serve for the moral betterment of these lesser classes.

When conflicts surfaced between market gunners on one side and sportsmen on the other, it was immediately apparent that the market hunters held the weaker hand. Though market gunners had the support of hotel and restaurant owners, they were not a wealthy lot, nor were they well organized. Yet while market hunters were certainly unhappy about the onslaught of legislation, game laws barely affected their work.

One reason that sportsmen were able to pass game laws so easily was that the laws asked so little of the state. Game codes specified fines for hunting or selling birds out of season, but appropriated no funds for their enforcement. Almost universally, these laws depended on citizens turning the perpetrator in, and very few had the occasion or motivation to confront an armed poacher or tattle on a neighbor.

Even when poachers or restaurants were accused of selling game illegally, glaring loopholes meant that few were ever convicted. After New York passed a strengthened game law in 1862, the sportsmen’s clubs that championed the legislation quickly identified fifty or sixty game dealers that violated it. Every one of them was able to escape penalty by claiming that their birds were purchased from out of state. Even though laws against poaching were “as valid as binding on the citizen as the law against burglary or highway robbery,” only two violators of New York’s law were convicted in as many years after its passage. Meanwhile, New York City continued to be the center of the national market in wild birds.6

Deficiencies in game laws were widely recognized and widely discussed, and sportsmen’s active lobbying led to constant fiddling with legislation in the attempt to land on more effective laws — short of appropriating state funds for their enforcement. One frustrated Forest and Stream reader responded in 1882 that “at every session of the Legislatures of the different States, we hear of proposed alterations and amendments of the laws, which those who advance them apparently think, will cure all our present evils. Tinkering with the game laws has become a regular part of the programme of our legislative bodies… Why can we not next year leave the laws as they are, and devote ourselves with all our energy to securing appropriations and the appointment of officers to enforce those that we already have?”7

The more clear-eyed among the sportsmen were willing to admit that they too were part of the problem. In a day of shooting, sportsmen regularly killed dozens or even hundreds of birds, far more than they or their families could ever eat. This unrestrained slaughter devastated game populations and opened the sportsmen up to accusations of hypocrisy. One critic complained that “If these humane sportsmen do any game preserving, they preserve it after it is dead; and if they protect it at all, they protect it from others so that they may have the exclusive privilege of killing it.”8

In 1882, one writer shared a sentiment that would have resonated at any point since the New York Sportsmen’s Club was founded forty years earlier: “Our supply of game is each year diminishing, because our laws for its protection are imperfect, are not properly enforced, and because of the foolish and wanton over-shooting which takes place at all points which are at all accessible.”9 Despite the proliferation of game protection societies and the widespread passage of laws they championed, the plight of the country’s birds had only gotten worse.

One disgruntled sportsman called the entire project of game protection into question. Writing to the magazine Forest and Stream and signing his name “Skeptic,” he argued that “a great deal of time and money is being wasted in the agitation of this question of game protection.” He pointedly asked sportsmen at large,

“will you be kind enough to tell me what adequate results there are – material results I mean – to show for all that you have said and done? Do not point, I beg, to the numerous game protective associations which have sprung up all over the land. I do not for a moment admit that they as a class can be spoken of with pride, for most of them have degenerated into mere pigeon shooting clubs and exert no influence in favor of the cause which you desire to forward.”

“Skeptic” looked at the laws then in effect and despaired that even the best enforcement mechanisms could counter the human greed which lay at the heart of overhunting. “The infinite selfishness of the human mind lies at the root of this matter, and until you can make sportsmen feel the respect for the abstract rights of others, which they would have others feel for theirs, your labor is in vain. Not until the millennial day will the golden rule be practiced.”10

Sportsmen deserve ample credit for creating the legal and administrative framework that would go on to successfully protect American wildlife. But as “Skeptic” pointed out, birds were still disappearing at an alarming rate. Outrage, organizing, and even laws and litigation had failed to meaningfully affect the downward trend in bird populations. Sportsmen had laid the groundwork, but it would take conservationists to pick up the baton, create a bigger tent, and lead a mass movement to protect birds before it was too late.

Harper’s Weekly, January 20, 1894, p. 70; Trefethen, James. “An American Crusade for Wildlife.” New York: Winchester Press. 1975.

Trefethen, James. “An American Crusade for Wildlife.” New York: Winchester Press. 1975.

Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times. Vol. 9, no. 22, p. 352. January 23, 1864; “National Sportsmen’s Association.” The Rod and Gun and American Sportsman. United States: Rod and Gun Association, September 12, 1874; Wildwood, Will. “The Sportsman's Directory.” United States: Fred E. Pond, 1891.

Smalley, A. L. (2022). The Market in Birds: Commercial Hunting, Conservation, and the Origins of Wildlife Consumerism, 1850–1920. United States: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 142; Palmer, Theodore Sherman. Chronology and Index of the More Important Events in American Game Protection, 1776-1911. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1912.

Palmer, Theodore Sherman. Chronology and index of the more important events in American game protection, 1776-1911. United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1912, p. 24.

Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times. “The Protection and Preservation of Game.” Vol. 10, no. 5, p. 65. April 2, 1864

“Firing In The Air.” Forest and Stream, July 6, 1882, p. 443.

“Letter to the Editor: Are They Monopolies?” Forest and Stream, September 15, 1881, p. 128.

“A Sign of the Times.” Forest and Stream, May 25, 1882, p. 323.

“What Does It All Amount To?” Forest and Stream, November 3, 1881, p. 270.