“An Innocent Recreation”: Shooting Pigeons for Sport

Pigeon-shooting contests were popular in the 1800s until animal rights activists shut them down — and passenger pigeons went extinct.

In 1883, the New York State Association for the Protection of Fish and Game faced a problem: there were no more passenger pigeons for their annual pigeon shoot. Every year, the Association’s assembly drew massive crowds with a pigeon-shooting contest that consumed upwards of twenty thousand birds, where contestants took turns blasting away at pigeons released from traps while spectators placed bets. For the previous twenty years, the birds had “very obligingly nested where they could be secured in the thousands by the professional netters and nest robbers hired by the Association, to be, after due course in transportation, offered as a sacrifice to the peculiar game protecting proclivities of the Association members.”1 But that year, the pigeons never showed up.

Americans had imported the sport of pigeon hunting from England in the 1820s and made it fully their own by substituting Europe’s rock dove for the local passenger pigeon. These birds were fast fliers, meaty targets, and most importantly, about as cheap as dirt. At one point, the eastern US was home to as many as five billion wild pigeons. A single roost might cover hundreds of square miles of forest, and their nests were packed so dense that they broke branches and toppled trees. Shooting the birds for sport (not to mention for food) seemed harmless enough, since no matter how many millions of birds were killed, there were always more to take their place.

So it came as an unwelcome surprise to the inappropriately named game protection association to find that there were suddenly no more pigeons to be had. One critic offered two possible explanations. Either “the pigeon has finally become tired of playing its rather arduous role in this burlesque of protecting the game and fish,” or “one added and two subtracted will, if kept up long enough, eventually exterminate even a pigeon flock.”2 As it turned out, the second theory was correct. Passenger pigeons disappeared from the wild within a decade, and the country’s recreational pigeon shooters would have to find something else to aim at.

A Champion At Every Crossroads

The sport of pigeon shooting started out at gun clubs, where it catered to affluent, urban participants. But by the 1870s the sport had spread so much that “there were shooting matches in every little town and a champion at every crossroads.”3

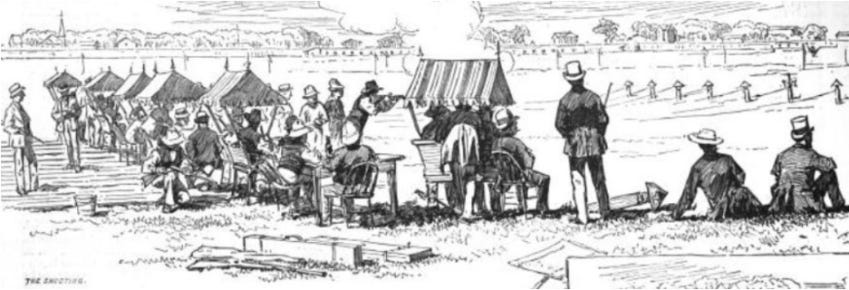

Trap shooting worked like this. Pigeons were placed in a row of baskets or traps about sixty feet away from shooters, who held shotguns loaded with birdshot. The contestants would take turns stepping up to the line and shouting “pull!”, at which point someone would tug a line releasing one of the birds from its trap, or just as often hurling it upward with a spring-loaded plunger. The shooter would then open fire at the airborne bird, and if it fell dead or injured within a certain distance from the trap, it would count as a point. If it managed to fly outside that ring, mangled or otherwise, it counted as a lost bird. It wasn’t so much an accomplishment to kill a pigeon as it was an embarrassment to miss one, and the shooter that scored the most birds claimed the prize.

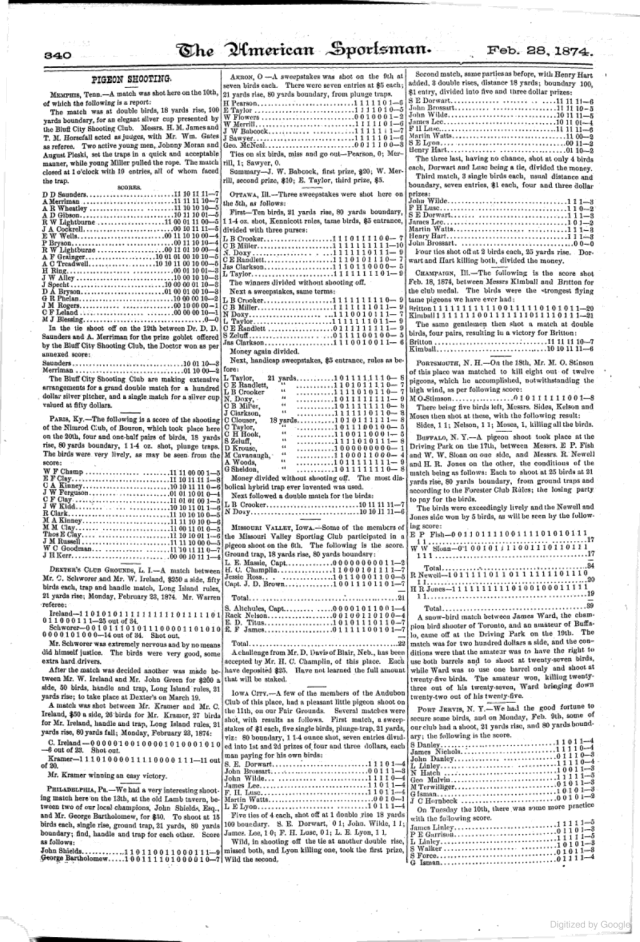

Many of these competitions were modest affairs, although they drew plenty of attention whatever the size. The sportsman’s magazine Field and Stream reported the results of trapshooting competitions from gun clubs throughout the country, which in 1872 ranged from a Christmas day “pigeon pop” in Flatbush, where a five dollar fee bought twelve competitors the chance to shoot five birds for a fifty dollar pot, to a $1,000 duel between the champion shooters of Luzerne and Schuylkill county, Pennsylvania.4

But some competitions were enormous. The New York State Sportsmen’s Association regularly hosted tournaments that consumed twenty thousand birds. In 1874, Henry T. Phillips, a major game merchant, shipped 34,416 pigeons packed in 478 coops, each holding six dozen birds, to supply the Leather Stocking Club Tournament in Oswego, New York.5 The number of pigeons that died before the shooting even began speaks to the conditions in which these birds were held. At one Missouri competition, only one third of the 60,000 birds supplied for the event survived transportation and confinement long enough to serve as targets.6

The only way to catch enough live pigeons to meet the insatiable demand of the country’s pigeon-shooters was to trap the birds near their enormous roosts using giant nets. These nets, which could reach twenty feet by forty, were rigged to spring over a patch of ground that had been baited with grain or salt. As an additional enticement, netters employed captive birds, called stool pigeons, as decoys. They would tie these birds to a padded stool on one end of a short teeter-totter, and at the approach of a flock of wild birds, would vigorously work the contraption up and down, forcing the captive bird to hover and land. When executed well by both netter and pigeon, this action might persuade passing pigeons that landing was safe, whereupon a pigeoner would spring his trap.

The right spring of a net might capture more than a thousand birds, and more than a thousand men might gather to trap birds at a single roost. These pigeons became just one more commodity flowing toward the East coast, “as much an article of commerce as wheat, corn, hogs, beeves, or sheep.”7

Pretty Coarse Butchery

Unsurprisingly, the slaughter and mutilation of millions of pigeons for entertainment attracted the unwelcome attention of early animal rights groups, who lobbied to get the sport outlawed. Activists described how it was the lucky bird that was killed immediately, as many a pigeon had its “…legs shot off, or its bill torn to pieces, or its body otherwise mangled, but retaining the ability to fly.” These escaped birds might survive for days, “living and dying in agony.”8

But beyond being cruel, the sport’s biggest flaw was that it was unmanly. “If an infuriated dove would now and then turn upon the gentlemen with double-barrelled guns,” suggested one writer, “the sport would be dignified by the addition of an element of remote danger.”9 Another noted sarcastically that pigeon shooting “doesn’t sound manly, but it must be a manly, noble sport, or gentlemen and ladies would not so love it.”10 These activists were not opposed to hunting wild birds, who “[enjoy] every opportunity for concealment or escape.” But releasing pigeons, “which are the very emblems of innocence” only to be immediately shot was little more than “butchery, and pretty coarse butchery at that.”11

Pigeon-shooters went to great lengths to defend their sport against these allegations. By their logic, the sport was no more cruel than butchering the birds for market. Pigeon hunting wasn’t wasteful, since the pigeons were “sent to the market and become articles of food.” Knowing that they were destined for someone’s dinner, shooters claimed that “these birds are in better condition for the table, from the care which has been taken of them, than are those which are killed especially for this use.”12

But then again, pigeon shooters argued that it was never really about a bird’s wellbeing. Paraphrasing Thomas Macaulay, one argued that the puritanical animal rights activists hated pigeon-shooting, not because it gave pain to the pigeon, but because it gave pleasure to the spectator.13

Perhaps more importantly, pigeon shooting was an issue of equity — and racial dominance. Its defenders argued that “men of leisure and riches only can go to a distance where wild birds can be found,” and “the man of less means” who was “unable to leave the settled part of the country” should be able to “enjoy such sport as he can find near by.” If nothing else, pigeon-shooting was a mark of racial superiority. “The love of field sports … so ancient, so pure, so healthy, so free from vice, so desirable of preservation by judicious legislation” was “an Anglo-Saxon element of character” that spread “wherever the Anglo-Saxon race has settled.”14

Adequate Replacements

In Massachusetts, ever the hotbed of progressivism, animal rights activists persuaded legislators to pass the country’s first law banning the shooting of captive birds in 1879. Several other states quickly followed suit. But even in states where the sport remained legal, pigeon-shooting would disappear almost entirely within twenty years.

As hunters liquidated pigeon flocks and farmers leveled the forests where they lived, eastern sportsmen had to import birds from further and further afield. After the 1850s, great flocks had stopped appearing near Raleigh, North Carolina and by 1870 passenger pigeons had become “rather scarce in New England.”15 All the while, there was “no end of pigeon trap-shooting.” After seeing the “millions of birds [that] have been taken from the nesting grounds and brought to the great annual tournaments of the State game protective associations,” one writer concluded in 1883 that “the fate of the wild pigeon is sealed.”16 Though they couldn’t have known it, 1882 was the year of the last major nesting event for passenger pigeons. Twenty years later, the last pigeon was killed in the wild.

Trap shooters had always kept alternative targets up their sleeves for when pigeons were scarce. There were, of course, the domesticated pigeons that were popular in England, bred for their small size and quick, zig-zagging flight. American sportsmen who could afford to be particular sometimes also used these birds, though they were less popular with the masses. Some shooters substituted house sparrows in a pinch, while in New Orleans “bat shooting was quite popular for a few years, but again public sentiment stepped in and this form of sport was dropped.”17

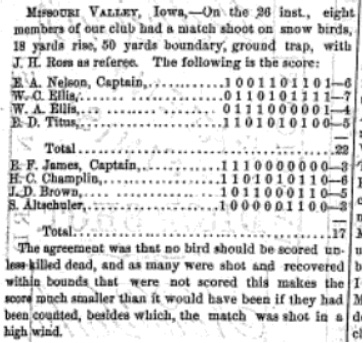

The most popular live substitute might have been the “snow-bird”, a term which included a range of small, sparrow-like birds, but usually meant dark-eyed juncos. In 1875 the sporting magazine The Rod and Gun reported that “Pigeon shooting in Chicago has come to an untimely end from lack of birds, and, now-a-days, snow-bird shooting is all the go.” In one week sport shooters killed more than two thousand of the birds, and champion shooters were “practicing on snow birds by the hundred.”18

But even before pigeons disappeared from the wild, trap shooters were working to come up with an inanimate replacement. The champion pigeon shooter Captain Bogardus developed glass balls that could be launched into the air as targets. Millions of these balls, filled with feathers, bells, smoke, and countless other modifications, were sold to shooters,. But a better replacement — the one still used today — came soon after. In 1881 one animal rights group described the novel invention as a “‘bird’ [that] is made of clay, and baked hard; [and] shaped like a saucer with a small rim turned in toward the centre.” Flung from a spring-loaded arm, the clay pigeon’s motion was “much more like the live birds than the glass balls, and is certainly less dangerous to man and beast, when broken about the fields.”19

Clay pigeons proved immediately popular, both among shooters and defenders of animal welfare, who celebrated that “there is far more trap shooting now than there was before the use of live birds was forbidden by law.”20 It made shooting both more accessible and affordable for the masses “who would never find the time to go off in search of game,” but could now “easily spend an hour or two of an afternoon at the traps.”21 Clay pigeons couldn’t stop the extinction of their wild counterparts, but in the eyes of shooters they proved a more than adequate replacement. An 1884 advertisement in American Field promised that “the use of this invention will largely fill the void in trap-shooting made by the scarcity of the wild pigeon.”22

Pigeon Shooting Staggers On

Hounded by animal rights activists, outlawed in many states, suffering from the loss of the passenger pigeon, and superseded by the more affordable and humane clay pigeon, the sport of live pigeon shooting staggered weakly into the 20th century. By 1906 live pigeon shooting had become “a thing of the past.” And while enthusiasm for the sport would occasionally resurface, a 1927 book on trap shooting remarked that “the interest is nothing compared to the old days.”23

Yet while it has receded from the public eye, pigeon shooting never fully disappeared. Today’s pigeon shooters, in deference to the public disdain for their sport, seclude their events in private shooting clubs in the east or on remote ranches in the south. Even so, animal rights activists will disrupt pigeon shoots with protests and drone fly-overs, as they did in 2015 at a pigeon shooting fundraiser for former US Senator Jim Inhoffe of Oklahoma. Meanwhile, around five million Americans shoot clay targets every year, and every clay pigeon they destroy is a bird’s life saved.

“Pigeon Versus Protection.” Forest and Stream, vol 21 no. 9. September 27, 1883.

Ibid.

Greenberg, Joel. A Feathered River Across the Sky: The Passenger Pigeon’s Flight to Extinction. United States: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014, p. 112

Forest and Stream, vol. 1, 1873, p. 332, 411

W. B. Mershon. The Passenger Pigeon, 1907, p. 103.

Joel Greenberg. A Feathered River Across the Sky. 2014. p. 89

W. B. Mershon. The Passenger Pigeon, 1907, p. 103.

“Pigeon-shooting.” Our Dumb Animals. United States: Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals., 1879.

Ibid.

Our Dumb Animals. United States: Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals., 1879.

“Pigeon-shooting.” Our Dumb Animals. United States: Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals., 1879.

“Pigeon Shooting at Tournaments.” The Rod and Gun and American Sportsman. United States: Rod and Gun Association, June 20, 1874.

Leffingwell, William Bruce. The Art of Wing Shooting: A Practical Treatise on the Use of the Shot-gun. United States: Rand, McNally, 1895.

Stackpole, J. L.. Argument for the Remonstrants Against the Bill Prohibiting Pigeon Shooting. United States: A. Mudge, printers, 1879.

Forbush and Job. A History of the Game Birds, Wild-fowl and Shore Birds of Massachusetts and Adjacent States. 1912. p. 442.

Forest and Stream. United States: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1884.

Mermod, Alec. “Trap Shooting.” Outdoor America. United States: Izaak Walton League of America., 1927.

The Rod and Gun and American Sportsman. United States: Rod and Gun Association, 1875.

Our Dumb Animals. United States: Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals., 1881.

“Pigeon Versus Protection.” Forest and Stream, vol 21 no. 9. September 27, 1883.

Forest and Stream. United States: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1884.

Price, Jennifer Jaye. Flight Maps: Adventures With Nature In Modern America. United States: Basic Books, 1999.

Mermod, Alec. “Trap Shooting.” Outdoor America. United States: Izaak Walton League of America., 1927.

Thank you for this fascinating piece. In my ignorance, I’d never known the origin of the expression ‘stool pigeon’.

Long time birdwatcher, just recently discovered your Substack and glad to subscribe. I'm so glad we're not doing this kind of destruction anymore.

Your photo comparison of the Passenger Pigeon and the Mourning Dove early in the post got me wondering -- I assume the Passenger Pigeon was targeted (literally) in part due to size, but it made me wonder if we had any idea of the population size comparisons between that bird and the Mourning Dove and the other pigeon we know well today - the Rock Pigeon. Was it by far the largest population and so therefore the obvious target, and now we are left with the obvious successors? Or maybe something else. I can go and do some more research online but wondered if you had already encountered such data.

Also, I hadn't realized that the "Snow Bird", aka Dark-eyed Junco, had ever been considered as a substitute! I have both the Mourning Dove and the Dark-eyed Junco coming to my feeders daily right now (in Central Ohio), though I expect the juncos will be heading north pretty soon.

Thank you.