Economic Ornithology

Before pesticides, birds were a farmer's best defense against bugs. And the government’s economic ornithologists could tell you exactly how much each bird was worth.

How many dollars is a Blue Jay worth to a farmer?

It seems illogical, and even a little profane, to assign a dollar value to a bird. Today, birds seem completely irrelevant to crop yields, and many of them are severely threatened by habitat destruction and pesticides from farming.

But a hundred years ago, birds were seen as the best remedy for the weeds and insect pests that threatened the country’s food supply and cost farmers hundreds of millions of dollars every year. And in order to identify the precise impact that birds had on agriculture, a field called economic ornithology was born. According to one of its leading practitioners, economic ornithology was “the study of birds from the standpoint of dollars and cents … in short, it is the practical application of the knowledge of birds to the affairs of everyday life.”1 And from the 1880s to the 1930s, birds were widely seen as economic agents, working alongside farmers in the fight against the insect hordes.

By the 1940s, economic ornithology had become discredited and obsolete. Effective and affordable pesticides had entirely replaced the birds’ bug-killing role, while economic ornithologists could never prove that their methods actually increased the number of helpful birds. But before their role in agriculture was dismissed, there was a time when we believed that we depended on birds for our food, and for our very survival.

The Bureau of Biological Survey

The idea that birds were helpful allies in the battle against insect pests was around long before the field of economic ornithology. But until the late 1800s, this idea was based on a belief in a rational or divine natural order in which all species, created by God or providence, had a role to play. Birds “are the barrier, which the benevolent Creator has set against the inordinate multiplication of the insect tribes,” said the American Agriculturist in 1859, “and they can not be hunted, and driven away from our cultivated fields, without destroying the harmony of God’s providential arrangements.”2

Yet by settling the country, leveling the forests, and turning prairies into cropland, settlers had upended this supposedly primeval equilibrium. “Nature when left to herself has balanced these forces evenly, so that the insects are kept by birds and other natural checks from becoming excessively numerous and destructive. But man has upset Nature’s balance.”3

The plagues of insects in this unbalanced world caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage to America’s crops each year. Based on the belief that any “disturbance of the proper balance between the feathered and insect tribes” affects “the food, the health, and the life of man,”4 the US Department of Agriculture established the Section of Economic Ornithology in 1885. The following year it became the Division of Biological Survey, and was upgraded to the Bureau of Biological Survey in 1905.

The role of this government unit, and of the entire nascent field of economic ornithology, was not to refute these earlier lines of thought about the relationship between birds and agriculture, but to provide rigorous quantitative and scientific proof of their accuracy. Specifically, these economic ornithologists were tasked with determining the economic status of birds and categorizing each species, authoritatively, as helpful or harmful to crops.

Bugs in Bird Bellies

In 1916, Gilbert Trafton summarized the primary approach used by economic ornithologists: “The practical value of birds to man, whether helpful or harmful, depends chiefly on their food habits,” and by examining what they eat, “the exact economic status of a bird is determined.” Sometimes this was done by observing the behaviors of birds in the field, but it usually meant dissecting birds and seeing what they had in their stomachs.5

Most of these stomachs were collected by researchers themselves, but many were sent by public-minded individuals wishing to contribute to science. In 1903, the Saturday Evening Post, for example, published a request that “every person in the United States who kills a bird is requested by the United States Government, not in a mandatory way, but as a matter of courtesy, to send the stomach and its contents to Washington.”6

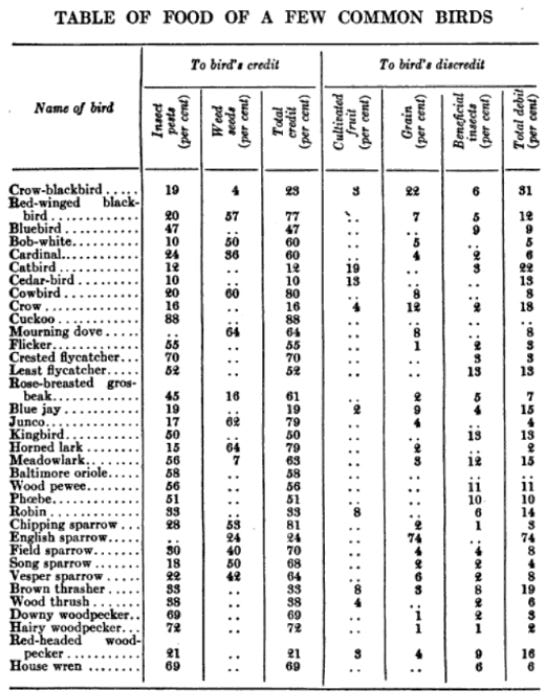

By 1916, the Bureau of Biological Survey had collected and analyzed the contents from more than 60,000 bird stomachs, which they used to determine whether each of the 400 species they studied was, on balance, helpful or harmful to man. Researchers divided the stomach contents into “good,” “bad,” and “neutral” categories, based on whether the partially-digested bug and plant matter was beneficial or harmful to farmers. Looking at the balance of a bird’s food, economic ornithologists could issue confident quantitative pronouncements on the economic status of birds. The robin was proven to be a “beneficial” bird, for example, because 33 percent of its food was “composed of insects harmful to man” compared to just 15 percent that is “composed of materials beneficial to man” (the remaining 52 percent was “neutral”).7

Economic ornithologists expressed an astounding level of confidence about their conclusions. Findings of the Bureau of Biological Survey “may be relied upon as perfectly trustworthy,” wrote Olive Thorne Miller in 1899. “The officers of the government of the United States, who have carefully studied the matter and found out positively, without guesswork, what birds eat, have declared emphatically that every bird they have examined does more good by destroying pests, than harm to our crops, excepting only the bird we have imported — the English or house sparrow.”8

Good Done by Birds

After the turn of the century, conservationists, as well as much of the general public, had a justifiable fear that many species of birds might soon disappear if drastic action were not taken for their protection. Thanks to overhunting, Passenger Pigeons and Carolina Parakeets had disappeared from the wild, and many ducks, swans, and egrets seemed destined for the same fate. The devastation brought out by insect hordes, without birds to hold them at bay, felt like an immediate threat. The famous ornithologist Frank Chapman said that “economic ornithologists now agree that, without the services rendered by birds, the ravages of the animals they prey upon would render the earth uninhabitable,” while National Geographic predicted that if birds disappeared, “not only would successful agriculture become impossible, but the destruction of the greater part of vegetation would follow.”9

With these statements in mind, the claim that “every bird that lives on insect life is worth its weight in gold to mankind”10 did not seem like much of an exaggeration. According to the Bureau of Biological Survey, native sparrows, who are “specially efficient destroyers of weed seeds,” saved farmers $35 million in 1906 by eating ragweed and crabgrass seeds. And during Nebraska’s 1874 Rocky Mountain Locust infestation, a single Marsh Wren was calculated to have fed her brood of chicks enough grasshoppers to save $1,743.97 worth of crops.11

The Bureau of Biological Survey even helped rehabilitate the reputation of some birds that were historically seen as enemies to the farmer. By examining over a thousand crow stomachs, the Bureau found that while crows did in fact pull up sprouting corn and nibble corn on the stalk, they ate more “noxious insects and mice,” meaning that “the verdict was therefore rendered in favor of the crow, since, on the whole, the bird seemed to do more good than harm.”12 Owls, which were long considered poultry thieves, were proven to eat enough mice to earn back “the small commission they collect” by nabbing the occasional chicken.13

Believing in Birds

These findings did not just live in obscure government reports. They came to be widely believed and repeated by farmers, sportsmen, conservationists, and the general public. From the 1880s to the 1930s, economic value became a dominant lens through which Americans thought about the relationship between birds and people.

To share the findings of their research, the Bureau of Biological Survey regularly published bulletins directed at educating farmers about the economic value of birds, with titles such as “Seed Planting by Birds,” “Hawks and Owls from the Standpoint of the Farmer,” and “Birds as Weed Destroyers.”14

But economic ornithologists also had plenty of help from local chapters of the Audubon society, whose members also saw birds as economic agents. In 1915, for example, the South Carolina Audubon Society brought “exhibits showing the usefulness of birds” at state and county fairs, while the New Hampshire Audubon Society reported frequent “inquiries from granges for information about the economic value of birds.”15

The League of American Sportsmen invoked findings from economic ornithologists to limit hunting of particularly helpful bird species. The League’s president praised quails as an obvious solution to farmers’ pest problems, writing that “cotton-growers lost annually one hundred million dollars; wheat-growers, another hundred million by the chinch bug and two hundred millions by the Hessian fly,” while “one quail killed in Ohio had 1,200 chinch bugs in its craw, and another killed in a Kansas wheat field had 2,000 Hessian flies.”16

The impact of economic ornithology was even felt in schools. The 1924 Maryland School Bulletin stated as a matter of fact that “insects would destroy all vegetation within a few years if it were not for birds,”17 while elsewhere children were given math problems that reinforced the view that birds were economic agents. Gilbert Trafton’s 1916 book Bird Friends offered some sample word problems, such as:

A pair of wrens were observed to feed their young 17 times in an hour. The parents fed their young from 5 A.M. till 8 P.M., and the young remained in the nest 15 days. Assuming that one insect was brought at each visit, how many insects were destroyed by this brood of wrens?

Ohio’s Department of Public Instruction said that the fight to protect birds was “not sentimental but economic.”18 Subscribers to the Saturday Evening Post read that birds were “the most effective means of killing the insects which last year levied a toll of six hundred million dollars upon the farmers,” making it a matter of “not bird protection, but self protection.”19 And in the General Federation of Women’s Clubs Magazine, Harriet Meyers wrote, with considerable alarm, that “without [birds] to destroy the vast horde of insect pests, there would be no vegetable life, and, consequently, no animal life, including that of man.”20

Birds, Forgotten

Yet by the 1930s and 1940s, few people believed that birds were the best strategy for controlling insect pests. This was partly because effective pesticides were being developed, which were more reliable than depending on nature’s balance. Yet people had also lost faith in the field of economic ornithology itself. While they could tell you that precisely 47 percent of a bluebird’s diet consisted of harmful insects, economic ornithologists could not tell you how to predictably increase their number on your farm. Nor could they tell you how your crops would be impacted by an increase in birds — an impact that entomologists increasingly claimed was marginal.21

As soon as farmers stopped seeing birds as a resource for controlling bugs and weeds, they generally stopped thinking about birds at all — or went back to seeing crows, blue jays, and robins as crop-stealing pests. And besides, birds were becoming less and less common on farms. With the rise of pesticides and industrial monocropping, fields of corn and grain had become inhospitable to the birds that once called farms home.

While it’s been mostly forgotten, the field of economic ornithology rose and fell during a unique time, an era when government ornithologists used modern statistical methods to model a robin’s annual consumption of caterpillars, while farmers tilled their fields with horse-drawn plows and prayed that the right kind of birds would move in. And in our own time, when the harms of pesticides and industrialized agriculture have never been more apparent, maybe we should take another look at the good birds can do.

Palmer, T. S. “A Review of Economic Ornithology in the United States.” US Department of Agriculture. 1899.

American Agriculturist. New York, May 1859. Volume 18, no. 5.

Trafton, Gilbert Haven. Bird Friends: A Complete Bird Book for Americans. United States: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

Dodge, J. R. 1865. “Birds and Bird Laws.” in Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture for the Year 1864. Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 433.

Trafton, Gilbert Haven. Bird Friends: A Complete Bird Book for Americans. United States: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

The Saturday Evening Post. United States: G. Graham, 1903.

Trafton, Gilbert Haven. Bird Friends: A Complete Bird Book for Americans. United States: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

Miller, Olive Thorne. The First Book of Birds. United States: Houghton, Mifflin, 1899.

Trafton, Gilbert Haven. Bird Friends: A Complete Bird Book for Americans. United States: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

Timmons, John. “Homes for Insectivorous Birds.” Harper’s Weekly. United States: Harper’s Magazine Company, 1913.

Trafton, Gilbert Haven. Bird Friends: A Complete Bird Book for Americans. United States: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

Ibid.

Baxter, Leon H.. Boy Bird House Architecture. United States: Bruce publishing Company, 1920.

Trafton, Gilbert Haven. Bird Friends: A Complete Bird Book for Americans. United States: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

“Reports of State Societies, and of Bird Clubs.” Bird Lore. United States: Macmillan Company, 1915.

“Killing Birds is Costly.” State of Ohio Department of Public Instruction. Arbor and Bird Day Proclamation, Ohio Arbor Day Program. Bulletin No. 2, Whole Number 14. 1916.

Maryland School Bulletin. Maryland State Department of Education. 1924.

State of Ohio Department of Public Instruction. Arbor and Bird Day Proclamation, Ohio Arbor Day Program. Bulletin No. 2, Whole Number 14. 1916.

The Saturday Evening Post. United States: G. Graham, 1907.

Meyers, Harriet. “How We Befriend the Birds.” General Federation of Women’s Clubs Magazine. United States: General Federation Magazine, volume 16, 1917.

Evenden, Matthew D. “The laborers of nature: economic ornithology and the role of birds as agents of biological pest control in North American agriculture, ca. 1880–1930.” Forest and Conservation History 39, no. 4 (1995): 172-183.

Note that nearly all of the diet data from these late 19th and early 20th c. Biological Survey studies have been entered and summarized (along with other more recent data) in the Avian Diet Database which can be explored here: https://aviandiet.unc.edu/.

Yet again, learned something new! Excellent information, thanks ‼️