For just ten cents a show, movie-goers had their choice of silent films showing at the Annapolis, Maryland Republic Theatre during the week of January 25, 1916. The Destroying Angel told the dramatic (to some, sordid) tale of a young starlet whose succession of lovers all meet an untimely end. For a lighter option, viewers might have chosen The Lamb, a comedy Western where a frail New Yorker gets to prove he’s not a weakling. For those with children in tow, however, the more appropriate option would be The Spirit of Audubon.

Sitting down to watch The Spirit of Audubon, viewers would have been treated to a two-reel film (running about 30 minutes) that was part drama, part nature documentary, and fully propaganda for the Audubon Society. The plot follows a young girl who is a valiant protector of birds and a young boy who enjoys robbing their nests. After fighting about the proper treatment of birds, both children have the same dream, in which they are visited by the “spirit of Audubon.” This ghostly figure was “much pleased with the little girl, but angry with the boy for not loving birds.” Audubon’s ghost then spirited them away on a journey throughout the country, visiting the “homes of the pelicans, tern, laughing gulls, ibises, and other birds,”1 who they observed “making their nests, feeding their young, making love in bird fashion and doing all the hundreds of things that make birds interesting the world over.”2

When he awakes, the repentant boy rushes to apologize to his young friend, and finds her at a “big Audubon celebration, which is being held by lovers of birds in honor of the big man who first went on record as the friend of the little feathered things.” After becoming enraptured with the parades and speeches, the young boy and his father pledge to join the society, and the film closes as “the spirit of Audubon rises above the top of the monument and smiles lovingly at his latest adherents.”3

During the Silent Film era, the Audubon Society and other conservation-minded individuals created dozens, if not hundreds, of motion pictures. Some of these, like The Spirit of Audubon, were dramas produced in collaboration with major studios, meant to entertain and educate. Many more were documentaries shot by nature photographers to be used in classrooms and on the lecture circuit. And like most films created in this era, almost all of them have been lost or destroyed — including The Spirit of Audubon. Yet the glimpses that remain, whether in newspapers, photographs, or even the occasional surviving reel, give us some amazing insights into how Americans first viewed birds on the big screen.

Capturing The Spirit of Audubon

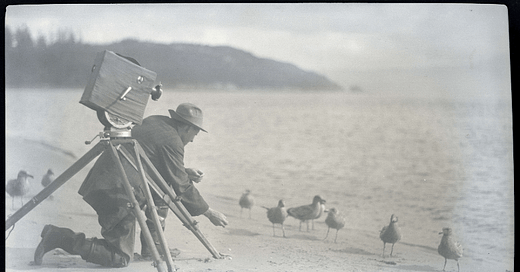

In the summer of 1915, The Thanhouser Film Company, producer of The Spirit of Audubon, provided the ornithologist, nature photographer, and Audubon Society officer Herbert Job with a “motion picture outfit” to capture the nature scenes for their film. Traveling down to the Gulf coast, Job spent two months recording scenes of pelicans, herons, gulls, and skimmers nesting, feeding, and caring for their young in wildlife refuges along the Florida and Louisiana shore.

For part of the trip, Job was accompanied by former president Teddy Roosevelt, who had created the wildlife refuges that appeared in the film while he was in the White House. Job turned his camera on the ex-president during their trip, and some footage of the incomparably charismatic Roosevelt was included in The Spirit of Audubon. This marked Teddy’s first (and possibly only) appearance in a “photo drama,”4 where he “incidentally came in for a bit of posing along with the birds,” and was shown “watching gulls, herons, wild ducks and other specie of wild fowls which circle and wheel about him.”5

In his summer of filming, Job captured enough footage to complete The Spirit of Audubon, and then some, bringing home almost three miles of film. Footage from this trip was also used for at least four other now-lost nature films released in 1916, including Wild Birds at Home, Ex-President Roosevelt’s Feathered Pets, Egrets and Herons,and Where Wild Fowl Winter. Incredibly, not all of the footage was lost — some of it was included in a film released ten years later called Roosevelt, Friend of the Birds, which you can watch on the Library of Congress website.

Filming Nature

The Spirit of Audubon was not a unique production. The Massachusetts Audubon Society also released a silent film that mixed documentary footage with plot and actors in their 1920 dramatization of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, The Birds of Killingworth, which tells the story of the dire consequences a town faces when the citizens decide to kill all of their birds. The film soundlessly combined “birds on the screen, singing and nesting, the thrush pouring out his soul in careless rapture” with “the wholesome human-interest story of New England village life of a century ago.”6 The Audubon Society advertised the film as “a worth-while story of interwoven birdlife and human life, teaching the lesson of bird protection and kindness for all.”7 One magazine predicted that the film “will be seen during the coming year by a million children.”8

Yet far more numerous than these “photo dramas” were nature documentaries. Every Audubon bulletin I looked through from the 1910s and ‘20s referenced educational moving pictures — sometimes dozens of them — that captured the country’s bird life. Some of these were produced by major motion picture companies, such as the Fox Film Corporation’s 1922 Feathered Camp Intimates.9 Many more were produced by the Audubon Society, “in order to meet the demand for high-grade educational material, both on the theatrical circuit and for schools and colleges.”10 In 1921 alone, they released seven films from the Pacific Coast states “on the theatrical circuit” through Goldwyn and the Bray Pictures Corporation, including The Climbing Mazamas, “showing mountain climbers on their trip to the top of Mt. Rainier with some of the wild folk they met.”11

Yet even these mark just a fraction of the bird films from the silent era. Government and conservation organizations produced their own outpouring of films. Individual filmmakers like Herbert Job and the incredibly prolific William Finley regularly produced their own moving pictures. And many other named and unnamed ornithologists and videographers captured and released nature films that were used in classrooms, shown in theaters, or accompanied lectures.

Flocking to Film

After it debuted in New York City on October 19, 1915, The Spirit of Audubon was advertised and distributed in theaters from Maryland to Minnesota and New York to Utah. While the Audubon Society did not profit financially from the film, they did expect it to result in “an advantageous publicity and a spreading of the educational propaganda.”12

It didn’t hurt that the movie had access to a built-in distribution network. In 1915, the Audubon Society boasted two million adult members in chapters located in six thousand towns throughout the country, in addition to over five hundred thousand Junior Audubon Society Club members.13 And each of these chapters was to be “notified by letter and through the society’s periodical, ‘Bird-Lore,’ of the release of the picture and will be urged to utilize its exhibition at theaters for spreading bird knowledge.”14 Audubon members were told to “induce managers of local theaters to obtain and exhibit this beautiful and instructive production, in order that it may be seen by children everywhere.”15 The Newark Evening Star promised that “schools and clubs will arrange for attendance in great bodies.”16

And schools, communities, and Audubon chapters followed through. The Spirit of Audubon was shown, for example, at the Children’s Hour in the Brainerd and Alden libraries in Minnesota,17 as well as at the thirteenth annual meeting of the Michigan Audubon Society “as a treat to the visitors and delegates.”18 In public schools, as in Erie, NY, the film was part of a broader bird-oriented curriculum that included bird-house building contests.19

Beat ‘Em or Join ‘Em

Adapting to film was just one more way that Audubon societies changed with the times. “As everyone knows,” said the president of the Illinois Audubon Society in 1916, “with the coming of the movies, great difficulty is found in many communities in getting any kind of a crowd to attend a lecture of an educational character.” But by arranging with a theater to “run several reels and then allow an hour for the lecture,” they could guarantee a standing-room-only crowd, and “whether persons wished to or not, they heard an illustrated talk on the economics of bird life.”20

For Audubon Society chapters throughout the country, showing films soon became an incredibly popular activity. In 1921, the Maryland Audubon Society, for example, held “one evening of moving pictures, loaned by the United States Department of Agriculture,”21 while the Oregon Audubon Society paired motion pictures with lectures every Saturday.22 The Wyncote, Pennsylvania Bird Club counted it their most important event of 1922 when they purchased “a moving-picture machine for our very own,” which “served to gather large audiences to hear the more serious and personal side of bird-work,” and to show “some beautiful bird and animal pictures.”23

Found Footage and The Heath Hen

Seven years after filming the nature footage for The Spirit of Audubon, Herbert Job traveled to Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts “to secure a motion-picture film of the vanishing Heath Hen … before the race might become extinct.”24 After centuries of overhunting and habitat destruction, there were fewer than 50 of this Eastern subspecies of Greater Prairie Chicken left, almost all of whom were male.

Though Job likely didn’t know it, he was living out the last days of the silent film era at the same time as he was documenting the end of the Heath Hen. The Jazz Singer, the first “talking” film with synchronized video and sound, was released in 1927, and by 1928 only one Heath Hen was left. In the birds’ final years, conservationists scrambled to preserve the vanishing Heath Hen, but their efforts came too late.

As silent films passed into obsolescence in the 1930s, there was no sense that these dying films might also need conserving. Studios cleaned the films out of their warehouses to make space for talkies. Fires in storage vaults destroyed the last copies of other irreplaceable works of history and art. And many moving pictures simply deteriorated out of existence — the nitrate film on which they were recorded was not meant to last a century. Less than 30 percent of all studio-produced silent films still exist, and this number is undoubtedly much lower for the sort of small-scale nature documentaries produced by Audubon.

Herbert Job’s 1922 film of the Heath Hen is lost, as are most silent films, and all Heath Hens. And while there’s not much hope for finding a wayward flock of Heath Hens, lost films do occasionally resurface. One such moving picture was discovered in 2015 by Edward Minot in his mother’s basement: a single reel from 1932 documenting the last Heath Hen, which now constitutes our last record of this marvelous, extinct creature.25

There is something poetic about a found film documenting a lost bird. Art and historic records are both precious and ephemeral, and through these old films we can remember, appreciate, and better understand bird and human life from long ago. Yet the value of these precious and fleeting recordings is inconsequential when compared to a being like the Heath Hen — a unique kind of life, forged over millennia, quickly snuffed out, and unforgivably irreplaceable. I’ll keep hoping for more of these lost films to show up, just like I’ll keep hoping for a remnant flock of Heath Hens to reappear. In the meantime, we need to do everything we can to make sure that no one else joins its ranks.

Moving Picture World and View Photographer. United States: World Photographic Publishing Company, 1915.

“Thanhouser: The Spirit of Audubon.” Moving Picture World and View Photographer. United States: World Photographic Publishing Company, vol. 26, p. 852. October 30, 1915.

Ibid.

“In Movie Land.” Rock Island Argus. November 19, 1915.

Moving Picture World and View Photographer. United States: World Photographic Publishing Company, 1915.

“Motion Pictures: ‘The Birds of Killingworth.’” Bulletin of the Massachusetts Audubon Society 1, no. 7 (November 1920): 5.

Ibid.

“The Fun of Seeing Things.” The Guide to Nature, vol. 14, no. 4. United States: Agassiz Association, 1921, p. 59.

“Report of Herbert K. Job, Department of Applied Ornithology.” Bird-lore. United States: Macmillan Company, 1922.

“Report of William L. Finley, Field Agent for the Pacific Coast States.” Bird-lore. United States: Macmillan Company, 1922, p. 406.

Ibid.

“Report of Herbert K. Job, Department of Applied Ornithology.” Bird-lore: A Bi-monthly Magazine Devoted to the Study and Protection of Birds and Mammals. United States: National Association of Audubon Societies., Vol. 16-17, 1915.

“Films for Bird Protection.” Newark Evening Star and Newark Advertiser. October 23, 1915.

Ibid.

“Report of Herbert K. Job, Department of Applied Ornithology.” Bird-lore: A Bi-monthly Magazine Devoted to the Study and Protection of Birds and Mammals. United States: National Association of Audubon Societies., Vol. 16-17, 1915.

“Films for Bird Protection.” Newark Evening Star and Newark Advertiser. October 23, 1915.

Minnesota Library Notes and News. United States: Library Division, Department of Education, State of Minnesota, 1915.

“Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the Michigan Audubon Society.” Selection from the William B. Mershon Papers, University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library. January 6, 1917.

“Spirit Audubon Is Film Shown At Erie School.” The Rock Island Argus and Daily Union. April 7, 1922.

“A Bird Talk in the Movies.” The Audubon Bulletin. United States: Illinois Audubon Society. 1916.

“Reports of State Societies and Bird Clubs: Wyncote (Pa.) Bird Club.” Bird-lore. United States: Macmillan Company, 1922.

“The Audubon Societies: The Oregon Audubon Society.” Bird-lore. United States: Macmillan Company, 1922.

“Reports of State Societies and Bird Clubs” Bird-lore. United States: Macmillan Company, 1922, p. 519.

Job, Herbert. “The Imperiled Heath Hen.” Bird-lore. United States: Macmillan Company, 1922.

“The Heath Hen and Other Early Ornithological Films of Alfred Otto Gross.” Special Collections and Archives, Bowdoin University. August 3, 2018.