Before we get started, I wanted to say thank you for reading Bird History! I recently opened up paid subscriptions to help support the work that goes into this research, and I explain more about this decision and the benefits of subscribing here. So if you make it to the end of this piece and learn something interesting, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my work.

After fleeing an extermination order by Missouri’s governor, after being chased by mobs from Illinois, after a grueling trek across the Great Plains, and after a blessedly mild winter, the Mormon pioneers were finally established in Utah’s Salt Lake valley. They felt a moment of peace, knowing they were a thousand miles from persecution in a land seemingly prepared for them by God. The crops they planted late upon their arrival in 1847 gave them just enough food to make it through the winter. Now, as their wheat stalks bent under the weight of the grains soaking up the summer sun, the pioneers felt they were finally secure in their promised land.

But then came the crickets.

These “wingless, dumpy, black, swollen-headed” bugs came not by the dozens, not by the thousands, but by the millions. A torrent of crickets swept down from the mountains, devouring everything in their path, coming like a biblical plague. Forty years after the event, the historian Hubert Bancroft wrote about how the “vast swarms of crickets, black and baleful as the locust of the Dead Sea … left behind them not a blade or leaf.” The Mormon leader Orson Whitney, rising to a similarly dramatic peak, remembered how the “army of famine and despair, rolled in black legions down the mountain sides.”1

The pioneers needed their grain crop to succeed if they were to survive another year. One settler recalled how the pioneers “fought and prayed, and prayed and fought the myriads of black, loathsome insects” using every strategy imaginable. They stomped on the crickets, and set them on fire. They dug ditches around their crops and filled them with water. They swept crickets off the wheat stalks with brooms and ropes. But no matter how many crickets they destroyed, more kept coming.2

Just when it seemed things couldn’t get worse, one more threat emerged on the horizon. Thousands of seagulls rose from the Great Salt Lake and headed straight for the almost-ravaged crops. But these birds were not interested in wheat. They had come for the crickets.

The gulls landed in the fields and immediately began attacking the pests. They stuffed themselves to bursting with crickets, took a drink of water, vomited the bugs right up, and went back for more. Orson Whitney dramatically recounted the events in 1888, writing that “the white gulls upon the black crickets, [were] like hosts of heaven and hell contending, until the pests were vanquished and the people were saved.”3

The pioneers did not hesitate to call this a miracle.

In his memoirs written seventy years later, John Young reminisced that “we should surely have been inundated, and swept into oblivion, save for the merciful Father's sending of the blessed sea gulls to our deliverance.” And towards the end of his life, the president of the Mormon church Joseph F. Smith recalled how he and his fellow pioneers were “literally preserved from starvation by the welcome visits and persistent efforts in the destruction of the devouring hordes by these beautiful winged saviors, which we esteemed as the providence of God.”4

This, at least, was the story I heard growing up in the Mormon church (more officially, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints). It was just one miracle among many demonstrating how God looked out for His chosen people. Stories like these were a separate category of historical fact than the moon landing or the civil war, but they were just as real. They didn’t rely on photographs or primary sources, but testimony from church leaders and repetition in Sunday School lessons. They were at once an affirmation and a test of faith, universally accepted and unquestionably divine. Digging into the details might risk shaking other foundations.

After I left the church, stories like these have only become more fascinating. More often than not, I find that there’s at least a glimmer of historical fact behind the miracle. And like any good story, miracles have a way of growing with time.

Of course, the miracle of the gulls as I heard it was one of biblical proportions. Did crickets literally sweep down from the mountains in waves, and did gulls actually stop them from devouring the pioneers’ crops? Did the saints – as Mormons like to call themselves – experience the event as a miracle at the time, or did God’s hand only become clear in retrospect? Primary sources can’t tell you whether it was God that sent the gulls, but they can indicate whether gulls came in the first place.

Fortunately, someone already did the leg work of answering these questions. In 1970, the historian William Hartley took another look at this miracle to figure out how much was legend and how much was fact, and published what he found in the Utah Historical Quarterly. To help evaluate these questions, Hartley looked at settlers’ diary entries during the cricket infestation and compared them with the narrative that became widely accepted.

Right off the bat, the element of the story that seems most fantastical – so many crickets that they blackened the earth – is also the one that’s the most literally accurate. We’re familiar with descriptions from centuries past of birds so numerous they block out the sun or fish so plentiful you could cross a river by walking on their backs. But to modern readers, these numbers stretch credibility, exceeding anything we’ve seen in today’s world so depleted of its biodiversity.

And so I too assumed that these descriptions of crickets must have been exaggerated. But while I was researching this piece, I was stunned by photos of cricket infestations that have continued in the American west. In fact, because of the 1848 infestation, the insect is still commonly known as the Mormon cricket (much to the chagrin of entomologists, since they’re a type of katydid and not true crickets, and to Mormons, who don’t love the association). Mormon crickets can swarm with a density as great as a hundred crickets per square meter and ravage thousands of square miles of farmland. A 1939 swarm infested more than 19 million acres of land, and as recently as 2002 there was an infestation that ravaged 2.4 million acres in Utah, Nevada, and Idaho.5

Diary entries establish pretty clearly that the saints were experiencing one of these cricket plagues. On May 27, 1848, Mrs. Lorenzo Dow Young wrote in her diary that “the crickets came by millions, sweeping everything before them. They first attacked a patch of beans for us and in twenty minutes there was not a vestige of them to be seen. They next swept over peas, then came into our garden; took everything clean. We went out with brush and undertook to drive them, but they were too strong for us.”

Around that time, settler accounts started including references to the arrival of gulls in letters and diaries. On June 9, for example, church leaders in the Salt Lake Valley wrote in a report to Brigham Young that "The sea gulls have come in large flocks from the lake and sweep the crickets as they go.” And the gulls kept eating crickets for week after week. The report from June 21 stated that "Crickets are still quite numerous and busy eating but between the gulls and our own efforts and the growth of our crops we shall raise much grain in spite of them." These writers certainly saw the gulls as helpful, but stopped short of calling their arrival a miracle. And as the crickets persisted for weeks after the gulls arrived, it might be a stretch to say they arrived in the nick of time.6

The most interesting thing that Hartley found when he reviewed pioneer diaries, however, was that many of them made no mention of gulls at all. The diary of Mrs. Young, referenced above, as well as several others who provided regular accounts of the advance of the crickets and the devastation they left behind, said nothing about gulls in any of their June entries, when crickets were at their worst and throughout the weeks that gulls intervened. This might suggest that the gulls’ impact was either quite localized, or that not all of the pioneers found it remarkable.

Regardless of their actual scale, it only took a few months for the gulls’ arrival to become widely accepted as miraculous. On September 28, Henry Bigler, who was away in California during the summer, wrote what he heard once he returned to Salt Lake:

The whole face of the earth I am told was literally covered with large black crickets that seemed to the farmers that they [the crickets] would eat up and completely destroy their entire crops had it not been for the gulls that came in large flocks and devoured the crickets. ... all looked upon the gulls as a God send, … that He had sent the white gulls by scores of thousands to save their crops.

Five years later, this miracle was shared for the first time in the church’s General Conference, and the intervening years had given the story ample opportunity to grow. Orson Hyde, who was then the president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, called the event “one that was never known to exist before, and never since to any extent.”7

In fact, the cricket scourge that threatened the Mormon settlers was not limited to 1848. For several years after, crickets again swarmed down from the mountains. And every time they did, it seemed the gulls were there to meet them.

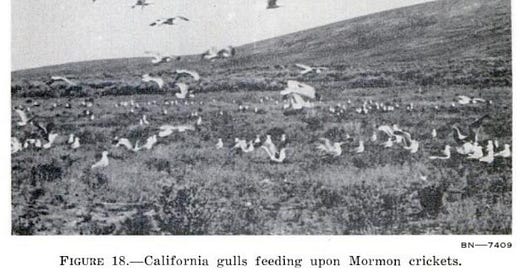

And so it has been every time the crickets have swept down the mountains. Whenever crickets break out, birds are never far behind. It’s the rare miracle you can predict and see in action. Nearly every record of cricket infestations, affecting saints and sinners alike, is accompanied by stories of hungry birds feeding on the massing insects. At an outbreak in North Dakota in 1921, thousands of gulls were seen feasting on crickets. The same was true in 1924 in Montana, and in Colorado two years later. In 1933, as many as one million gulls gathered to eat crickets in Saskatchewan in a feeding frenzy that lasted weeks.

And it’s not just gulls that eat crickets. In April 1849, a church report described another cricket infestation in Salt Lake, but wrote with relief that “large flocks of plover have already come among them, and are making heavy inroads in their ranks.” Hawks too are known to feast on crickets during infestations, with one 1889 observer counting more than five hundred circling over a swarm of bugs. A 1959 review by the U.S. Department of Agriculture found records of blackbirds, magpies, turkeys, robins, ospreys, sparrows, vultures – nineteen kinds of birds in all – that were known to feast on the insects. But the same report cautioned dryly that “Undoubtedly gulls destroy many Mormon crickets, but experience has shown that they cannot be depended upon solely for control.”8

“Ye statesmen and state-makers of the future! … What shall [Utah’s] emblem be? Name not at all the carpet-bag. Place not first the beehive, nor the eagle; nor yet the miner's pick, the farmer's plow, nor the smoke-stack of the wealth-producing smelter. Give these their places, all, in dexter or in middle, but whatever else the glittering shield contains, reserve for the honor point, as worthy of all praise, the sacred bird that saved the pioneers.” — Orson Whitney, in his 1892 History of Utah.

Last December, I dragged some friends with me to visit the state capitol building in Salt Lake City. Inside, we found the building filled with gull iconography. The building’s dome, soaring 285 feet above the rotunda, is painted with hundreds of gulls circling overhead. Utah’s House of Representatives is itself represented by a great seal featuring two gulls. A few blocks south, in Salt Lake’s Temple Square, stands a gold-plated memorial to the gulls, commissioned by the Mormon church in 1913.

Utahns have always given gulls a special place for the service they provided the pioneers. Early on, Utah’s territorial legislature passed laws making it a crime to harm gulls. As a 1926 report from the Bureau of Biological Survey wrote, gulls were “held almost sacred in Utah,” and pioneer diaries back up this assessment. In his pioneer memoirs, John Young wrote how he could “never hear their sharp, shrill cry but my heart leaps with joy and gladness,” and that they should “ever be remembered, protected, and sacredly cherished by the children of the Latter-day Saints.”9

Gulls enjoyed their designation as Utah’s unofficial state bird until 1955, when legislators realized that nowhere were they listed in the lawbooks and remedied the error. But for a state that holds its gulls in such high esteem, there’s always been a little ambiguity about which species of gull it has chosen for a symbol. Google Utah’s state bird, and every result will tell you that it’s the California Gull, which is the most common resident gull during summer and in all likelihood the bird that feasted on crickets in 1848. But if you look up the 1955 legislation designating Utah’s official bird, the state code simply lists it as the “sea gull.” Utah’s official State Symbols page does a little better, but still gets the species name wrong, listing it as the “California Seagull.”

Birders love ridiculing states for their unoriginal, geographically questionable, and taxonomically unsound selection of state birds. There are seven states that all chose the cardinal to represent their state, and another six that chose the meadowlark. Then there’s my home state of South Dakota that was unique in choosing a non-native bird, the introduced and gleefully hunted ring-necked pheasant. But no state gets more criticism than Utah for its California Gull. How could a state possibly choose a bird that’s named after another state? But legislative missteps and historical exaggerations aside, I’d argue that no state has made a better choice.

Kane, Thomas Leiper. The Mormons: A Discourse Delivered Before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania: March 26, 1850. United States: King & Baird, Printers, 1850; Bancroft, Hubert Howe. The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: History of Utah. 1889. United States: History Company, 1889; Whitney, Orson Ferguson. Life of Heber C. Kimball: An Apostle, the Father and Founder of the British Mission. United States: Kimball family, 1888.

Young, John R.. Memoirs of John R. Young, Utah Pioneer, 1847. United States: Deseret News, 1920; Bancroft, Hubert Howe. The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft: History of Utah. 1889. United States: History Company, 1889.

Whitney, Orson Ferguson. Life of Heber C. Kimball: An Apostle, the Father and Founder of the British Mission. United States: Kimball family, 1888.

Young, John R.. Memoirs of John R. Young, Utah Pioneer, 1847. United States: Deseret News, 1920; Talmage, James E. “Were They Crickets or Locusts, and When did They Come?” Improvement Era, Vol. 13 No. 2, December 1909.

Extension, USU, "Grasshoppers and Mormon Crickets: Fighting them for Nearly 100 Years" (2003). All Current Publications. Paper 1314. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/extension_curall/1314

Hartley, William. “Mormons, Crickets, and Gulls: A New Look at an Old Story.” Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 3. 1970.

Hyde, Orson. “Common Salvation.” Journal of Discourses, Vol. 2, Discourse 23. September 24, 1853.

Wakeland, Claude Carl. Mormon Crickets in North America. United States: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1959.

McAtee, Waldo Lee. The Role of Vertebrates in the Control of Insect Pests. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1926; Young, John R.. Memoirs of John R. Young, Utah Pioneer, 1847. United States: Deseret News, 1920.

Absolutely fascinating. Always learning stuff from your posts.

Fall 1847 was approaching the peak of Solar Cycle 9, Feb. of 1848 with 220 sunspots that month.

The cycle ended in 1855...and in the upswing of Solar Cycle 10, peaking in Jan. 1860, earth experienced the famous "Carrington Event" (Sept. 1859).

https://weather.plus/solar-cycle-9.php

Insect populations bloom relative to solar activity (both minima and maxima). It also appears that "pandemics" correspond, similarly. Not because of the bugs, because of the effects of space weather on a wide range of terrestrial protective systems.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9510177/

See also

The Solar Activity Cycles and the Outbreaks of the Gypsy Moth –

Lymantria dispar L. (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) in Serbia

MILAN MILENKOVIĆ and VLADAN DUCIĆ

(Sorry, there is no link I can find to paste where; link d/ls doc)

So whatever the underlying dynamic, you gotta love the gulls for taking advantage of the cricket surplus...and one might expect there was a gull surplus that year as well?

1933 was near the bottom of Solar Cycle 16.

1939 was at/near the top of Solar Cycle 17.

2002 was at/near the top of Solar Cycle 23.

https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2020/10/Tracking_the_solar_cycle_NOAA