The Italian Problem, Part I: Bird-Killing Foreigners

Italian immigrants in the early 20th century hunted and ate songbirds, which put them in direct conflict with American conservationists.

“Wherever there are large settlements of Italians,” wrote the prominent conservationist William Temple Hornaday in 1913, “the reports are the same. They swarm through the country every Sunday, and shoot every wild thing they see. Wherever there are large construction works, —railroads, canals or aqueducts, —look for bird slaughter, and you are sure to find it.”1

Americans have a long and tragic history of exploiting their country’s native wildlife. But by the time that Hornaday wrote these words in his highly influential book Our Vanishing Wildlife, decades of activism by conservationists had led to strict state and federal protections for birds. Almost universally, small insectivorous birds like sparrows, mockingbirds, goldfinches, swallows, and wrens were protected by law. Yet as soon as these activists could congratulate themselves for protecting their resident birds, they were faced by a new threat — Italian immigrants.

For America’s Italian immigrants, hunting songbirds was a pleasant escape from urban squalor and the oppressive routine of backbreaking wage labor. It was a way of reaffirming culture and tradition in a new and often unwelcoming country. It was a way to put a little extra food on the table, and earn a little extra income on the side. Song birds, after all, were an Italian delicacy. And in America, they were abundant and seemingly free for the taking.

In 1900, there were around one million Italians living in the United States. By 1915, this number had quadrupled. “The Italians are spreading, spreading, spreading,” warned Horniday. ”If you are without them to-day, to-morrow they will be around you.” Like any time a group of immigrants has come to the United States, “native Americans” (as white native-born citizens took to calling themselves) blamed the Italian immigrants for crime, disease, job loss, and cultural conflict. But this time they added a new grievance. They began worrying about the relationship and attitudes toward nature that immigrants were bringing to America, which was epitomized in the Italian practice of eating songbirds.

Uncivilized Slaughter of Song Birds

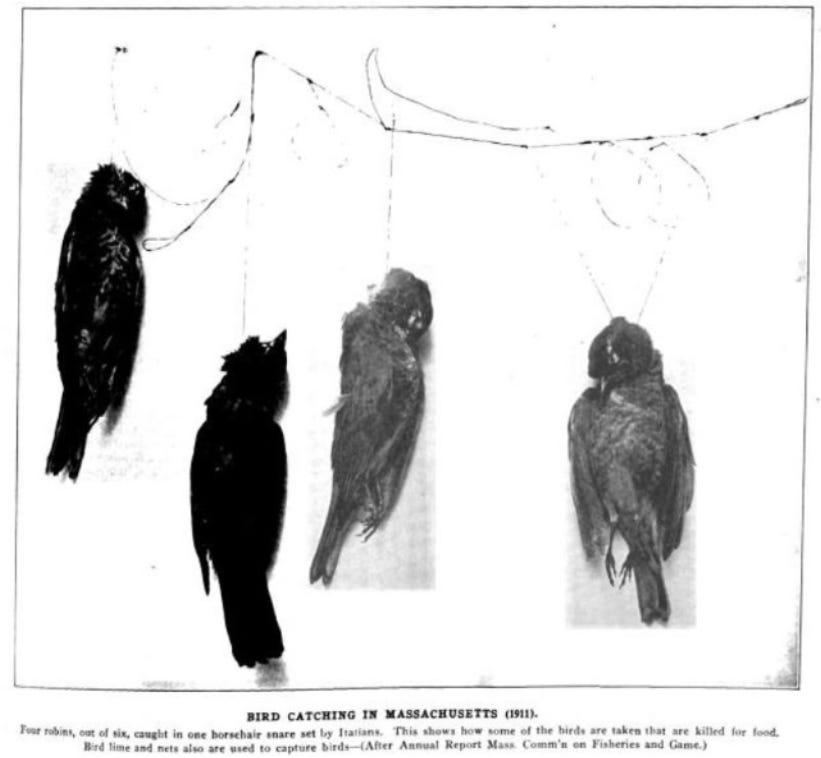

In 1915, there was a widely-reported case of two Italians who were tried in Hoosick Falls, New York, for killing wild robins. When brought to court, they confessed that they had “boiled alive and then eaten young robins and flickers which they had taken from their nests.”2 Because they couldn’t pay the hefty fine associated with the offense, they were each jailed for nearly two months. One game warden stated that he had “never heard of such uncivilized slaughter of song birds.”3 In another case, a game warden just outside of Boston found that “a gang of contract laborers practically cleared the woods of all birds in a section of town, leaving the earth about their camps strewn with feathers.”4

Stories like these were extremely common in conservation-oriented publications like Forest and Stream and the Audubon Society’s Bird-Lore, but as is often the case with racial profiling, authors readily mixed fact with invective and hearsay. “I have been told that if so much as a song sparrow gets up, the whole party shoots at it,” wrote the renowned ornithologist Edward Forbush in 1904. This “horde of foreigners, mainly Italians” would readily shoot songbirds “for sport, and it is said they are afterwards eaten.”5 And these views were widely held. A 1903 survey asked naturalists, Audubon Society officers, sportsmen, and hunters the factors they believed responsible for the decrease in the state’s bird populations. After blaming overhunting by sportsmen, the second most popular response was “Italians and other foreigners.”6

The killing of songbirds by Italians was not just seen as an immoral act. Italian hunters were considered a threat to birds that rose to an almost existential level. Songbirds were not just beautiful and innocent, they were a natural resource responsible for protecting the nation’s crops by eating insect pests. By killing songbirds, immigrants from Italy (“a country devoid of appreciation of the economic value of birds”)7 were a threat to the livelihood of farmers and the food supply of all Americans. Travelers to the Italian countryside were “struck by the utter absence of birds,”8 and Edward Forbush warned that if birds were not protected “from this European invasion, their numbers must soon diminish, as has already happened in some parts of Italy and other Mediterranean countries.”9

Tales from Italy

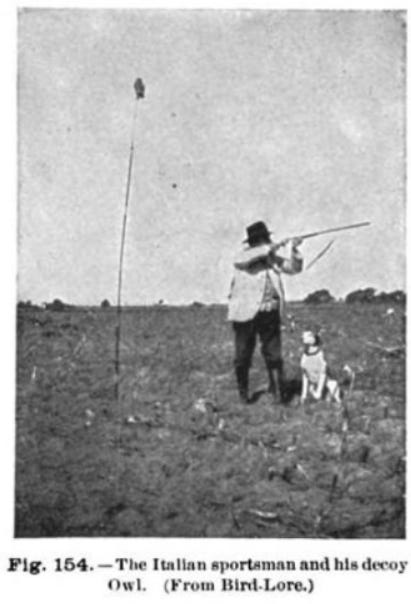

Americans looked to accounts from travelers visiting Italy to understand why Italian immigrants treated songbirds with such depravity. C. H. Ames, writing in Forest and Stream in 1906, described meeting some hunters outside of Rome, who proudly “opened their bags and displayed — five tiny little songsters, of the size of canary birds, and one of them with only a broken wing, but alive and bright eyed in its silent terror and pain. A more sickening and shameful sight I have not recently seen.” This experience led him to meditate “on conditions which make the Italian immigrant the indiscriminate shooter of everything that has life, and the foe of the game warden.”10

Readers found tales of the “low-browed, swarthy, ill kept” Italian hunter of songbirds, who lived in a “dirty and foul-smelling tower”, and encountered lurid details of his brutality: “A soiled hand seizes the struggling linnet … A sharp-pointed twig is thrust straight through the head of the helpless victim at the eyes, and after one wild, fluttering agony — it is dead.”11 The fruits of this bloody harvest could be found in Italian markets, where travelers saw “Robin Redbreasts, Thrushes, Sparrows, and other kinds piled up like grain along the walls.” Even the authors less inclined to be polemical had dismal views of Italians’ relationships with birds: “Italian birds are trapped and shot in incredible numbers … and are regularly sold in the markets as food for man and beast. There is no strong public sentiment in favor of the birds, and their service to agriculture is doubted.”12

Italian Pestilence

While there was no shortage of reports confirming that Italians did in fact kill and eat songbirds, the rhetoric directed against them was at best suspicious and generalizing, and at worst blatantly nativist. The upright moral reformers, refined defenders of wildlife, quickly debased themselves in their nakedly racist descriptions of the Italian immigrants. “No song bird or any other bird of the insect-destroying type is safe at any season” from the Italians, who “are almost primitive in their manner of life, are mostly abjectly ignorant, often filthy, and in their going and coming seem ignorant of all ideas of adaptation to the conditions around them, and with these is largely intermingled an acknowledged criminal class.”13

In his book Our Vanishing Wildlife, William Temple Hornaday dedicated an entire chapter to “Slaughter of Song-Birds By Italians”, where he warned the reader to “look out sharply for the bird-killing foreigner; for sooner or later, he will surely attack your wildlife.” The periodical Forest and Stream called the Italian an “intrepid and lawless forager … to whom all is grist that comes to the hopper.”14 These foreigners were “over-running suburban districts,” and would “cheerfully [invade] your fields, and even your lawn.” According to Hornaday, the Italian was “literally a ‘pestilence that walketh at noonday.’”

Italians were targeted as uniquely barbarous, and compared unfavorably with other Europeans. “The Italians do not feel those sentiments of friendship and affection for the song-birds of the country, so common in England and Germany, as well as in most parts of America,” said Francis Herrick in 1906.15 Poles, Slavs, Hungarians, and other Eastern Europeans were sometimes also blamed for killing birds, but Italians were unquestionably the greatest threat.

Writers grouped Italians with other enemies of birds, which invariably placed them among unflattering peers. One writer ranked the threats to song birds, in order, as “cats, small boys, English Sparrows, Italian laborers, and Starlings.”16 Another agreed, writing “To the cat the Sicilian is a close second; and a harder problem to deal with.”17 Italian men were constantly infantilized as the moral equivalents of boys or Native Americans. “Certain Indian tribes declare that all birds are good for food and may be eaten,” wrote one, “and the average small boy or Italian quite agrees with them.”18

What Can Be Done?

Most Americans who had anything to say on the subject advocated the strictest possible punishment for the foreigners caught killing songbirds. “Show the judge these records of how they do things in Italy,” said Hornaday, “and ask for the extreme penalty.”19 But there were others who argued that it was ignorance and poverty, rather than malice or some sort of congenital barbarity, that led Italians to kill songbirds. These reformers argued that education, rather than harsh fines and imprisonment, would be best for immigrants and best for birds.

In my next post, I’ll look at how conservationists, sportsmen, game wardens, and the Audubon Society tried to reign in this Italian terror through laws, punishment, education, and reform. While these actions would ultimately protect many songbirds — while costing the livelihoods and liberty of many Italian immigrants, as well as the lives of a score of game wardens — they would also transform hunting from a right inherent to the land into a privilege reserved for citizenship.

Hornaday, William Temple. Our Vanishing Wild Life: Its Extermination and Preservation. United States: C. Scribner's sons, 1913.

Trafton, Gilbert Haven. Bird Friends: A Complete Bird Book for Americans. United States: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

“General Notes: Italian Atrocities.” Bird Lore. United States: Macmillan Company, 1915.

Forbush, Edward Howe. “Robins Killed in the North.” Forest and Stream. United States: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1908.

Forbush, Edward Howe. Special report on the decrease of certain birds, and its causes, with suggestions for bird protection. Massachusetts State Board of Agriculture. 1904, p. 481

Ibid.

Trafton, Gilbert Haven. Bird Friends: A Complete Bird Book for Americans. United States: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

Holder, Charles. “Among the Wild Hyacinth.” Forest and Stream. United States: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1914.

Edward Forbush. Special report on the decrease of certain birds, and its causes, with suggestions for bird protection. Massachusetts State Board of Agriculture. 1904, p. 482-483

Ames, C. H. “For the Protection of the Killdeer.” Forest and Stream. United States: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, vol. 67, 1906.

Hornaday, William Temple. Our Vanishing Wild Life: Its Extermination and Preservation. United States: C. Scribner's sons, 1913.

Herrick, Francis. “Bird Protection in Italy as It Impresses the Italian.” Bird-lore. United States: Macmillan Company, 1907.

Culyer, John. “Italians Who Kill.” The Willimantic Journal (Willimantic, Conn.), August 27, 1909.

“Game Bag and Gun: In Western Pennsylvania.” Forest and Stream. United States: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1906.

Herrick, Francis. “Italian Bird Life as it Impresses an American Today.” Bird-Lore. 1906.

Rathborne, R. C. “Starlings as a Nuisance.” Bird Lore. United States: Macmillan Company, 1915.

Forest and Stream. United States: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, vol. 67, 1906.

“Feathers and Tariff.” Forest and Stream. United States: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1913.

Hornaday, William Temple. Our Vanishing Wild Life: Its Extermination and Preservation. United States: C. Scribner's sons, 1913.

I never heard this before! Thanks for sharing this.