Bringing Wild Birds Home

Colonizers never really succeeded at domesticating any of America’s wild birds, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t try.

While traveling through the South in 1905, the writer Dan Beard had the questionable pleasure of meeting an eccentric character in a small Georgia town who invited Beard over to watch him feed his chickens, a term which the man evidently used quite loosely. “At his call of ‘cluck, cluck’”, wrote Beard, “there appeared two sand-hill cranes, one purple gallinule, a number of wood ducks, bantams, game chickens, a lot of birds which I was unable to identify in the scrambling mass of fowl, and a big covey of bob-whites.” To all appearances, these normally wild birds had grown perfectly tame. Beard saw that “the birds were unconfined by any barrier other than a board fence, and as many flew to his call their wings could not have been cut.”1

From their very first settlement, European colonizers were impressed with the abundance, the diversity, and in particular, the meatiness of American birds. Hungry and ambitious settlers saw enticing possibilities to bring civilization to the country’s flocks as well as its people. And this sentiment proved durable. In his 1856 book The American Poulterer’s Companion, Caleb Bement described what many Americans felt when they looked at wild birds: “There are quite a number of beautiful wild fowl that, if domesticated, would not only make useful additions to the flocks of our poultry-yards, but add greatly to the beauty of those flocks.”2

For the most part, these dreams would go unrealized. Yet while they generally failed to induct new members into the barnyard menagerie of domestic fowl, amateur poulterers conducted a multitude of little-publicized backyard experiments with domestication until early in the 20th century. Many Americans abducted ducks, geese, quail, and grouse from their wild homes with the goal of breeding them in captivity to produce fat, docile, and ideally, flightless offspring. Keeping these wild birds at home blurred the line between domestic and wild, entering the ambiguous space between food and family pet. As Dan Beard summarized after his visit to the Georgia chicken coop in 1905, “While such sights are uncommon, and only to be seen in out-of-the-way corners of the country, there is scarcely a section of our land where some favorite covey of bob-whites have not been known to be partially or wholly domesticated.”3

Many Called, Few Chosen

John James Audubon, famous for his exhaustive catalog of paintings of America’s birds, learned much of what he knew about birds through hands-on experience. While living in Kentucky in the 1820s, Audubon purchased 60 Prairie Chickens (also called pinnated grouse), clipped their wings, and turned them loose in his garden. Within weeks, he found that they “became tame enough to allow me to approach them without their being frightened,” and “became so gentle as to feed from the hand of my wife.” After this experience, he concluded that “the Pinnated Grous is easily tamed, and easily kept. It also breeds in confinement, and I have often felt surprised that it has not been fairly domesticated.”4

But for the grouse, as for most birds on which it was attempted, domestication would remain perpetually just out of reach. “The prairie hen is said to be easily tamed, and with a little care might soon be domesticated,” wrote Caleb Bement in 1856.5 No more progress had been made by 1899, when A. F. Ackley predicted that if the pinnated grouse were domesticated, “there would be added to the feathered stock about the farm yard a fowl with excellent flesh, a new figure to please the eye, and probably a fairly good layer.”6

Audubon had just as much hope for America’s many wild ducks. He predicted that “very little attention would be necessary” to domesticate Eider ducks,7 while he found that the Blue-Winged Teal “soon becomes very docile” if kept in captivity, and believed it could “readily be domesticated.”8 He also shared the experience of a miller in New York who trapped a pair of Gadwalls, removed a joint from their wing to prevent their flight, and released them in his poultry yard. Each spring, the ducks would build nests and raise large broods of chicks, who would not leave the pond even though they could fly freely.9

Yet more than any of these, the Wood Duck was the most desired and elusive project for domestication. Stories of success could be found, like that of Captain Boice of Havre de Grace, Maryland, who, in the late 1700s, had “a whole yard swimming with wood ducks, which had been tamed and completely domesticated.”10 Nevertheless, forty or fifty years later, Audubon could only predict that “with a few years of care, the Wood Duck might be perfectly domesticated.”11 In 1856, Caleb Bement shared the same sentiment, writing that “many attempts have been made to domesticate that elegant and most beautiful of the duck tribe,” but evidently none were met with success.12

Low-Hanging Fruit

The only duck that Americans were actually able to domesticate was the Mallard, although they don’t deserve any particular credit for doing so. The Mallard’s native range extends across the entire Northern hemisphere, and whether it was in Asia, Europe, or North America, it seems that the birds were begging to be domesticated. “Wherever at any time in the history of the world male and female wild Mallards happened to be caught and kept in captivity,” wrote John Robinson in 1924, “a domestic race might be developed.”13 In fact, every breed of domesticated duck the world round, with the exception of South America’s Muscovy Duck, is descended from Mallards.

It was relatively common for European settlers to capture or hatch wild Mallard ducks and remove a joint in their wing to keep them from flying away. Within a few generations, their offspring “became as large as common ducks and lose their power of flight.”14 According to Audubon, “The squatters of the Mississippi raise a considerable number of Mallards which they catch when quite young, and which, after the first year, are as tame as they can wish.”15

Although most of the “improved races of ducks” found in 19th and early 20th century America were domesticated breeds brought over from Europe, it would be hard to tell the mongrel “puddle ducks” of European stock from those that descended from domesticated American Mallards, and given how easily and indiscriminately they interbred, there would be little point in distinguishing them anyhow.16 Wild Mallards become domesticated so quickly that they “cannot be distinguished from stock that has been domesticated for centuries,” and as late as 1913, wild birds were “still frequently captured and domesticated.”17 This intermingling proved to be such a problem for breeders raising mallards for game parks that in 1917 one writer lamented that he “did not think there was a stock of pure-blooded mallards on any of the game farms or any of the private game breeding establishments in the United States.”18

Prized Honkers

Canada Geese were also a tempting prospect for domestication, as they were regarded as “nearly as good and as profitable as the domestic goose, which they exceed in size, and especially in the quantity and quality of their feathers.”19 When farmers would find nests of wild geese, they would sometimes take the eggs and hatch them under hens “from the earliest years of settlement” of the colonies.20 And by the 1860s, Canada Geese were “not an uncommon inhabitant of the poultry yard, having been domesticated and even bred from.”21

Farmers found that Canada Geese would readily breed with domestic geese derived from European stock when given the opportunity, but like the mules produced by pairing horses with donkeys, their hybrid children were infertile. “The offspring of the Canadian and common goose are mongrels,” wrote Jedediah Morse in 1801, “and are reckoned more valuable than either of them singly, but do not propagate.”22 In the 1820s, these hybrids were “regularly offered for sale during autumn and winter”, where they brought “a higher price than either of the species from which they are derived,”23 possibly because they were both larger and “of a finer flavor” than their parents.24

But these birds weren’t just kept for their feathers, meat, and eggs, like domestic geese. Both captive-bred and wild-caught geese were kept to serve as live decoys, double agents unaware that their honking would bring wild geese flying overhead down into range of hunters. A hunter might keep a flock of twenty to forty of these birds, and would not likely sell their “prized honker” for $200.25

Yet however long Canada Geese were kept in captivity, some of their wildness remained. Every spring, the birds would “discover symptoms of uneasiness, frequently looking up in the air and attempting to go off. Some, whose wings have been clipped, have traveled on foot in a northerly direction, and have been found at a distance of several miles from home. They hail every flock that passes overhead.”26 By the 1920s, farmers had concluded that the Canada Goose was not suited for domestication at scale, largely because it “does not gain weight in domestication … and so does not become incapable of rejoining its wild relatives,” the trait that keeps domestic Mallards grounded.27

Better Left in the Wild

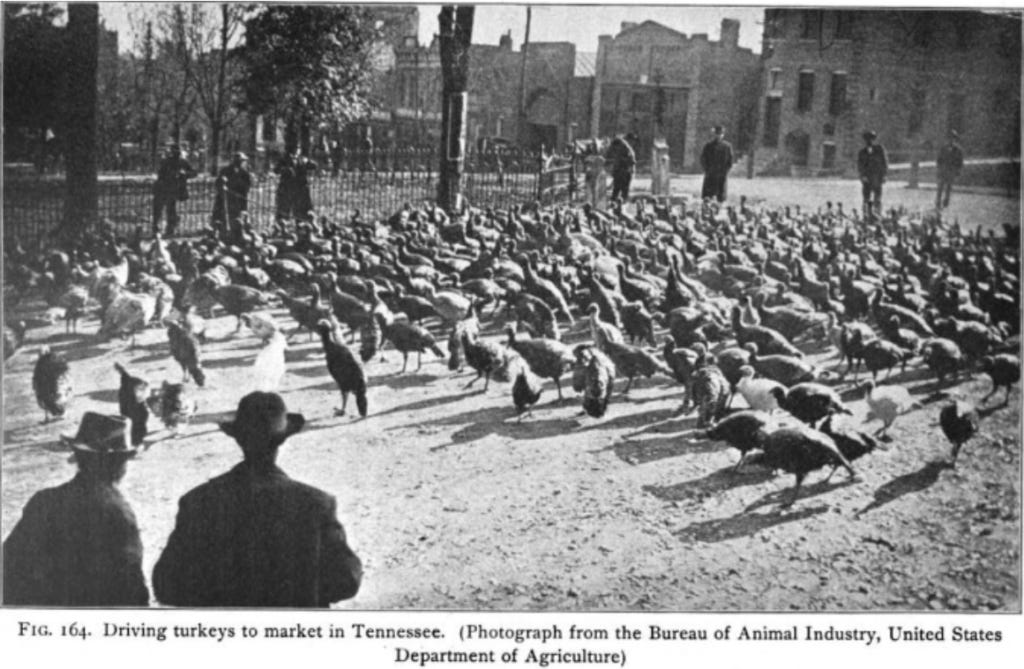

In 1835, Audubon wrote that “our attempts to domesticate many species of wild fowls, which would prove useful to mankind, have often been abandoned in despair, when a few years more of constant care might have produced the desired effect.”28 Yet after 400 years of colonization, European settlers largely failed to bring any of America’s native birds into the familiar barnyard lineup. The turkey, of course, has been domesticated, but colonizers can take no credit. The gobblers found on todays’ farms are the descendants of turkeys domesticated by indigenous Americans in Mexico. These transatlantic turkeys were abducted by Spanish conquistadors to Europe, carried back across the Atlantic to Jamestown and Plymouth colonies by the English, and then interbred with wild birds to form unique American breeds.

As the 20th century dawned, more and more Americans were deciding that wild birds did not need domesticating after all. Widespread market hunting and environmental degradation dramatically reduced the numbers of wild ducks and geese. The extinction of the Passenger Pigeon and near-disappearance of the bison led many to realize that our wild creatures were not only vulnerable and deserving of protection, but provided immense value to the public. John Robinson, the nation’s preeminent poultry expert, concluded in 1924 that “indeed, the wild birds are much more valuable to us in the wild state than they would be if domesticated.”29

Beard, Dan. “How to Plant Quail.” Outing, vol. 45 United States: Outing Publishing Company, 1905, p. 243.

Bement, Caleb N.. The American Poulterer's Companion. United States: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1856, p. 288.

Beard, Dan. “How to Plant Quail.”

Audubon, John James. “Ornithological Biography, Vol. 2: An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America.” Edinburgh: Neill & Co. 1833.

Bement, Caleb N.. The American Poulterer's Companion, p. 296.

Ackley, A. F. “The Prairie Hen.” American Poultry Journal. United States: American Poultry Journal, 1899, p. 385.

Audubon, John James. “Ornithological Biography, Vol. 3: An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America.” Edinburgh: Neill & Co. 1835.

Audubon, John James. Ornithological Biography, Vol. 4

Ibid.

Wilson, Alexander. American Ornithology: Or, the Natural History of the Birds of the United States, vol. 8. Philadelphia: Bradford & Inskeep, 1814.

Audubon, John James. Ornithological Biography, Vol. 3

Bement, Caleb N.. The American Poulterer's Companion.

Robinson, John Henry. Our Domestic Birds: A Popular Primer of Aviculture. United States: Reliable Poultry Journal Publishing Company, 1924, p. 127.

Robinson, John Henry. The Growing of Ducks and Geese for Profit and Pleasure. United States: Reliable poultry journal publishing Company, 1924, p. 34.

Audubon, John James. Ornithological Biography, Vol. 3

Robinson, John Henry. Our Domestic Birds

Ibid.

McIlhenny, E. A. “Pure Bred Mallard Versus Puddle and Call Duck.” Bulletin of the American Game Protective Association. United States: The Association. Vol. 6, no. 1. February 1, 1917, p. 5.

Bement, Caleb N. The American Poulterer's Companion.

Robinson, John Henry. The Growing of Ducks and Geese for Profit and Pleasure.

De Voe, Thomas Farrington. The Market Assistant: Containing a Brief Description of Every Article of Human Food Sold in the Public Markets of the Cities of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn; Including the Various Domestic and Wild Animals, Poultry, Game, Fish, Vegetables, Fruits &c., &c. with Many Curious Incidents and Anecdotes. United States: Hurd and Houghton, 1867.

Robinson, John Henry. The Growing of Ducks and Geese for Profit and Pleasure.

Audubon, John James. Ornithological Biography, Vol. 3

Thomas De Voe. The Market Assistant

Murphy, John Mortimer. American Game Bird Shooting. United States: Orange Judd, 1882.

Bement, Caleb N.. The American Poulterer's Companion.

Robinson, John Henry. The Growing of Ducks and Geese for Profit and Pleasure.

Bement, Caleb N.. The American Poulterer's Companion.

Robinson, John Henry. Our Domestic Birds: A Popular Primer of Aviculture.