Field Notes: Everyone Had a Feather Bed

Pigeon beds, superstitions, and good, hearty shaking.

While I’m researching my free bi-weekly articles, I find a lot of great tidbits, tangents, and delightful but not-quite-on-topic quotes that don’t make it to print. I offer Field Notes as a dispatch to paid subscribers that includes clippings from primary sources, stand-alone quotes, and snippets that got cut for time. This issue of Field Notes covers material that didn’t make it into last week’s post on feather beds.

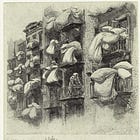

When communities were visited by a flock of passenger pigeons, they were deluged with a supply of birds larger than they knew what to do with. In his fantastic 2014 book A Feathered River Across the Sky, Joel Greenberg described how one family in Piermont, New Hampshire dealt with an enormous flock of pigeons that nested nearby in 1781. In ten days, the Tyler family caught nearly five thousand birds in nets, which was far more than they’d be able to process and consume themselves. So they invited their neighbors over for a “picking bee.” The neighbors walked away with the meat from all the pigeons they plucked, and the Tylers got enough feathers to stuff four beds.

No one knows how many passengers swept across 19th-century America. One estimate that Greenberg cites puts the number at five billion birds, and contemporary accounts suggest that more than a billion could gather in a single flock. In last week’s post, I quoted James Fenimore Cooper’s reaction to such a flock in his 1823 novel The Pioneers: “Here is a flock that the eye cannot see the end of. There is food enough in it to keep the army of Xerxes for a month and feathers enough to make beds for the whole country.”

If this statement was an exaggeration, it was a small one. The 1820 census counted 9.6 million Americans. If it took the Tylers 5,000 pigeons to stuff four mattresses, each mattress required the feathers of 1,250 pigeons. At that rate, plucking five billion pigeons could make four million beds. Assuming two people slept on every feather bed, then this would cover eighty percent of the country.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Bird History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.